Near-range LiDAR may monitor, warn Arctic ships about dangerous icing

The Arctic Council Working Group on the Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment (PAME) reported a 37% increase of ships in the Arctic during the 2013–2023 timeframe. The safety of seafarers and interests transiting within these waters requires the adoption of innovative technologies such as near-range light detection and ranging (LiDAR) to master this harsh environment.

Ship icing causes nearly 90% of the accidents within polar waters, according to Eirik Samuelsen, a researcher at the Norwegian Meteorological Institute. It occurs on vessels navigating within polar or subpolar waters, but can also occur at milder latitudes when masses of cold spray are flung onto a ship advancing against waves with winds at an air temperature just above or below the freezing point.

Icing impacts the efficiency of a ship by making the deck and its equipment unworkable—with serious consequences for cargo operations and the performance of deck-connected electronics. More importantly, icing adds mass to the ship structure that can dangerously decrease the stability of smaller passenger ships and of vessels with low freeboard (small distance between waterline and deck), such as fishing trawlers.

The recent sinking of American fishing vessels Destination (2017) and Scandies Rose (2019), and the Russian trawler Onega (2020) during heavy icing was a key factor in the loss of many lives and demonstrates that accurate forecasting of icing rates for seafaring is still in its infancy. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) standard 35106 acknowledges the lack of a model for sea ice spray prediction that covers a wide range of vessels and structures.

Empirical prediction methods

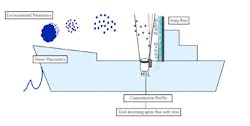

In the northern hemisphere, nearly 90% of the freezing spray derives from the cloud generated by the interaction of the ship and the sea water waves propelled by the wind (see Fig. 1). Empirical prediction methods associate some meteorology/oceanography (metocean) variables with the icing rates measured onboard ships. Based on a dataset of observations made during the early 1980s onboard 85 Alaskan ships, in 1990 James Overland (who now leads a U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration project on Arctic change detection, sea ice dynamics, and large-scale Arctic meteorology) formulated a method that involves considering seawater freezing temperature, the 2-meter air temperature, and the sea surface temperature to predict hourly icing rates. Predictions administered by the weather service are given in terms of light, moderate, heavy, and extreme icing accumulation on ship surfaces (see Fig. 2) or in millimeter/hour rates. He recently agreed that the inclusion of more parameters that impact the physics of the freezing spray—which influence the icing rates—could provide more precise predictions.

The Marine Icing model for the Norwegian Coast Guard (NoCG; MINCOG) formulated in 2016 by Eirik Samuelsen of the Norwegian Meteorology Institute includes more metocean data, plus selected ship and course details based on the accretion rates observed onboard three Norwegian Coast Guard vessels of the class NoCG “Nordkapp” navigating within the Barents Sea during the 1983–1998 timeframe.

Investigations into fatal icings of the three vessels above revealed considerable discrepancies between real life icing rates and hindcasts made using the parameters of the Overland and MINCOG methods, and the conclusion is that—no matter how many parameters they include—empirical models cannot yield predictions valid for any vessel under all circumstances.

They build on a handful of ship types and few observations of spray icing. Global warming is also altering the basic condition compared to when the observations were made. New, expensive, and global measurements on a wide range of ships are required to produce an effective model for any type of vessel and sea weather conditions.

Laboratory experiments

To obviate the lack of experimental data, Sujay Deshpande, then a Ph.D. student, simulated in 2020 the icing of sea spray in a laboratory of the Arctic University of Norway, where seawater with different temperatures from a cooling chamber reproduced the conditions of the sea, and was sprayed onto plates of different materials inside a freezing chamber reproducing the atmosphere. The sticking point in all prediction models is determining spray flux data consistently: Spray data gained on a real ship can be used only for that ship.

Deshpande identified seven critical parameters—air and water temperature, salinity, and wind speed are readily measurable, while spray flux, duration, and frequency are not. He used computational fluid dynamics to simulate the latter spray parameters to feed an artificial intelligence (AI) predictor. But reconstructing the real-life behavior of droplets ranging from 10 µm to millimeters under different sea, gravity, and wind conditions and by diverging temperatures and different liquid water content, remains of paramount importance for formulating prediction models that work.

In the past, mechanical and electronic devices based on some form of physical collection or registration of spray samples from a fraction of the cloud were installed on decks for field work to monitor sea spray live. By all their merits, a quite limited picture of the processes in the freezing cloud resulted and the data sets thus collected fell short in grasping the multifaceted phenomenon, calling for the implementation of a more advanced technology.

A game-changer: Near-range LiDAR

There is a long history of using elastic backscatter LiDARs with expensive high-energy pulsed lasers for atmospheric characterization at great distances. Recent advancements in high pulse repetition frequency lasers and eye-safe photodetectors widen the scope of atmospheric LiDAR applications to include shorter ranges. Further, Eduard Gregorio and colleagues at the University of Leida in Spain demonstrated that a near-range compact system based on light-emitting diode (LED) light sources and suitable avalanche photodetectors enable better observations and more efficient characterizing of pesticide dispersion at affordable costs in comparison to direct field particle sampling.

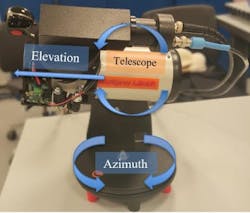

Based on this idea, Professor Sushmit Dhar at the Arctic University of Norway reasoned that a similar compact system could provide more comprehensive information on how water spray clouds behave and freeze on a ship’s deck and superstructures. With the goal of unprecedented quality of sea spray analysis, Dhar designed the MarSpray LiDAR (MSL) prototype for onboard icing research (see Figs. 3 and 4).

The MSL is a monostatic multiaxial experimental laser radar that features a 905-nm OSRAM SPL UL90AT08 indium gallium arsenide (InGaAs) laser diode semiconductor and a Hamamatsu PMT R5108 photomultiplier. Its pulse driver is a TIDA-01573 by Texas Instruments, and a 7-mm diameter aspheric lens with a focal length of 8 mm that works as an outgoing beam collimator. MSL’s 905-nm wavelength was selected because of the 60% zenithal summer transmittance of the atmosphere and the reduced impact of sunlight within that spectral range.

A Dobsonian mount supports the 76-mm f/3.95 Newtonian receiver of the assembly that collects the backscattered signal transmitted to the photomultiplier after being filtered by an interference bandpass filter with 70% transmittance at 905 nm and full-width half-maximum (FWHM) 25+5 nm. The latter is designed to suppress background disturbance from the environment and sunlight.

Dhar and colleagues tested the MSL assembly in the cold chamber of the Arctic University of Norway, where a nozzle located at a distance of 340 cm from the emitter sprayed water conically (see Fig. 5). The signal from the backscattered spray became visible at a distance of 285 cm, reaching its maximum at 335 cm. Pulses of 3 to 4 ns revealed concentration variations between 45 to 60 cm inside the cloud.

To compensate for the six degrees of translational and rotational motions imparted to the LiDAR when installed onboard a ship at sea, a correction algorithm incorporates the motion inputs derived from an inertial measuring unit.

By facilitating the acquisition of the not easily measurable parameters of spray flux, duration, and frequency, this “proof of concept” experiment reveals the potential of short-range marine LiDAR for characterizing icing sea spray with the required high temporal and spatial quality required to formulate realistic predictions using AI.

“We are now developing a more robust version of MSL that is both a weatherproof and portable system specifically designed for real-world maritime use, with a goal of making onboard installation more practical and efficient,” says Dhar. “This version will be tested at sea.”

Coupling LiDAR with AI may soon lead to an instrument that can warn seafarers in real time about the icing risks. “We believe it’s possible to develop a standardized sea spray LiDAR system that, together with AI, can deliver real-time data and early warnings to shipmasters about icing conditions during navigation. The system we are currently working on combines multiple sensors, including LiDAR, and a smart algorithm trained on a range of environmental scenarios. This allows it to detect patterns and provide timely alerts, which helps crews deal with ice accumulation before it becomes hazardous. The equipment can also be used to optimally control anti-icing measures, such as activating pre-warm heaters only when needed—improving both safety and energy efficiency. At this stage, I’m unable to share further technical details because it’s currently under patent evaluation,” Dhar says.

The era of life-threatening uncertainty of on-ship ice load is nearing its end.

FURTHER READING

E. Gregorio, X. Torrent, S. Planas, and J. R. Rosell-Polo, Sci. Total Environ., 687, 967–977 (2019); https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.06.151.

About the Author

Vittorio Lippay

Vittorio Lippay has been a member of the Institute of Physics since 2018 and a member of the Institute of Chartered Shipbrokers (London branch) since 2012.