This article is the fourth in Photonics IP Insights and Strategy, a monthly series designed to help scientists, engineers, entrepreneurs, and business leaders navigate the crucial area of Intellectual Property and keep them apprised of IP trends in various emerging photonics technologies.

Last month, we looked at the process of preparing and submitting a patent application, and getting that application granted as a patent. This month, we look at how that process can be used to build up a patent family, a number of related patents, from your original application. This is done using divisional applications and continuation applications.

Divisional applications

Before examining your patent application, the examiner may consider that it claims more than one invention; in other words, the application has independent claims directed to different inventions. In that case, the examiner may require you to restrict the application to only one of the inventions for prosecution. The patent statute states that an inventor can get a patent for “an invention,” and so the Patent Office takes the position that a patent should not cover multiple inventions. Also, the examiner has to search the prior art for each invention in the patent and it would be burdensome for the examiner to do prior art searches for multiple inventions for only an application fee.

As an example, if an application contained claims to an optical chip with a new type of optical circuit and claims to a new method of manufacturing the waveguides on the chip, such an application would be ripe for restriction. The new type of optical circuit might not require the new method of waveguide manufacture and could be made using conventional methods, while the new manufacturing method could find application in the manufacture of other types of circuits. Also, the examiner would have to search completely different technological areas to look for prior art in optical chip design and waveguide fabrication. Thus, in such a case the examiner would be justified in requiring restriction to one of the inventions for prosecution. The usual response to the restriction requirement is to select one of the inventions for prosecution, which is then examined in the usual way, as discussed in the previous article.

This does not mean to say that the second invention, which was not selected after the restriction requirement, is lost. You can file a second application to cover the second invention, in what is termed a “divisional application,” one that has been “divided out” from the original application. The divisional application uses the same specification and drawings as the parent application, and includes a “claim of priority” to the original application. The divisional application is given the same effective filing date as the parent application, even though it is filed sometime after the first application. This means that any publications or patents that come out after the filing date of the parent application (the “effective filing date”), but before the filing date of the divisional application, cannot be used against you as prior art.

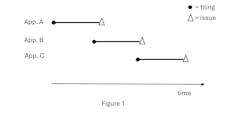

There is a time limit for filing the divisional application, however. It can be filed any time that the parent application is pending, but cannot be filed once the first application has issued as a patent. In the case where the restriction requirement identified more than two inventions, subsequent divisional applications can always be filed for the non-elected inventions so long as there is at least one pending application that claims priority back to the parent application. This situation is illustrated in Figure 1, which shows the filing dates and issue dates of a parent application (App. A), a first divisional application (App. B), and a second divisional application (App. C). Even though App. A has issued before App. C is filed, App. C can still make a priority claim back to the filing date of App. A because App. B, which also claimed priority to App. A, was pending when App. C was filed, and App. A was pending when App. B was filed.

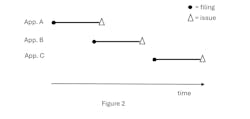

Figure 2 shows a situation where App. C is filed after App. B issues. In this case, App. C cannot claim priority back to App. B or App. A, because there was no pending application on which the App. C could claim priority when it was filed. If this situation was to occur, there may be more prior art that can be considered against App. C, and App. A and App. B may even be considered to be prior art to App. C.

Continuation applications

In some situations, you or your patent attorney may decide that the claims considered in an application do not completely cover the invention in the way that you wanted, you may decide there is an aspect of the invention that was not included in the original claim set, or you may decide that there are unnecessary limitations in the independent claim that you would prefer to be omitted. Regardless of the reason, you can file what is termed a “continuation application.” For example, if you had an application on a method of digitally analyzing a digital image and decided that one of the steps in the broadest claim was not necessary for the invention, then you could file a continuation application with a broader claim that omitted that step.

Continuation applications work in a similar way to divisional applications. They use the same specification and drawings as the parent application and must include a claim of priority to the application or applications to which you want to claim back. Also, the continuation application has to be filed while there is a pending application from which to claim priority. If there is no pending application, there can be no priority claim. The main difference between a continuation application and a divisional application is that the divisional application is filed after a restriction requirement where the examiner has stated that the different independent claims are directed to different inventions, while the continuation application can be filed for any reason.

Lifetime of continuations and divisionals

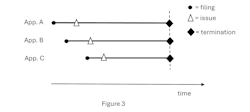

Continuation and divisional applications do not extend the lifetime of the patent coverage. The statute states that the life of a patent extends 20 years from its effective filing date. For continuation and divisional applications, the effective filing date is not the date on which they are filed, but the filing date of the earliest application to which priority is claimed. Figure 3 shows the lifetime of the patents that result from the applications in Figure 1.

There are some circumstances under which the lifetime of a patent can be extended beyond the 20 years, but those will be the subject of a later article.

Sophisticated portfolio owners use continuation and divisional applications to position themselves more strongly in their market space. A defensive position can be strengthened by creating a picket fence of patents around a set of products. An offensive position can be strengthened by using continuation applications to block market space for competitors and to develop patents that read closely on a competitor’s products. It is perfectly legitimate to fashion continuation claims to cover a competitor’s newly launched product, so long as the claims are enabled by, and contain a written description in, the specification.

Also, divisional and continuation applications may be used to unlock value hidden somewhere in your patent portfolio. In consultation with the client, a team of lawyers at my firm decided that a single application, that did not even cover any current client products, could be expanded into a family covering orthogonal frequency-division multiplexing (OFDM), important to the emerging 4G wireless standards. After filing multiple continuation and divisional applications from that original application, they developed a portfolio that the client sold for $75 million. You can read more about that story here.

Make sure to talk to your patent attorney about divisional and continuation application practices for your portfolio.

This article is the author’s opinion, not that of Laser Focus World or Carlson Caspers. The information presented here should not be relied upon as legal advice.

About the Author

Iain McIntyre

Iain A. McIntyre, J.D., Ph.D., is a partner at the Minneapolis law firm Carlson Caspers. He earned his doctorate in laser physics from The University of St. Andrews in Scotland. After working in lasers and electro-optics for 10 years, he switched careers and has worked in patent law for more than 25 years. He is experienced in patent prosecution, litigation, counseling, FTO, and due diligence analyses.