Tutorial: Writing and submitting a patent application

This article is the third in Photonics IP Insights and Strategy, a monthly series designed to help scientists, engineers, entrepreneurs, and business leaders navigate the crucial area of Intellectual Property and keep them apprised of IP trends in various emerging photonics technologies.

You’re working on a technical problem and come up with an idea of how to solve it, something new that you haven’t seen anyone do before. Your boss says the idea is so innovative that the company should patent it. What do you do?

Many companies have procedures for an inventor to prepare an invention disclosure, usually a brief two- to three-page description of the problem that needs to be solved and the new technical innovation that solves the problem. Usually, companies review invention disclosures regularly to prioritize which disclosures they should convert into patent applications.

Once there is a decision to proceed with the patent application, the patent attorney will review the disclosure and may interview the inventor to ask questions about the disclosure and explore the boundaries of the invention. The inventor can help the patent attorney by including as much detail in the invention disclosure as is reasonable—especially if the invention is in a technology the attorney is not an expert in. The attorney will ask you to review the application before filing. Please give this as thorough a review as you would any paper you’ve submitted for publication.

Patent application requirements

The contents of the patent application are set by statute and by Patent Office rules. A patent application includes a description of the background of the problem being solved; a summary of the invention; a detailed description of the invention, including a set of drawings if useful to describing the invention; and an abstract.

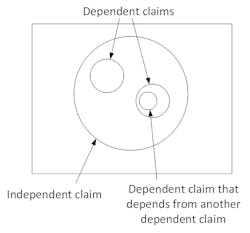

The application concludes with a set of claims defining the invention for which patent protection is being sought. There is at least one independent claim, which is the broadest description of the invention. There may also be one or more dependent claims that each include all the limitations of the independent claim, along with one or more additional limitations. The relationship of dependent claims to the independent claim is illustrated in the Venn diagram (see figure below). As the broadest description of the invention, the independent claim is the largest circle in the “invention space.” Dependent claims are the smaller circles within the largest circle. In some cases, a dependent claim contains all the limitations of another dependent claim, in which case it falls within the boundaries of that other dependent claim.

Patent review components

Once completed, the application is submitted to the Patent Office for review to ensure it contains all the necessary components. The application includes the correct fee and a declaration or oath from the inventor(s) stating that they provided authorization for applying and that they believe they are the original inventor(s) for the claimed invention. Neither the fee nor declaration/oath must accompany the application when filing it at the Patent Office. However, the examination process will not start until the Patent Office has received them.

The Patent Office has developed a classification system with a hierarchy of technical subject areas for classifying every application. The application is classified upon receipt, and the art unit associated with that classification receives the application and assigns it to an examiner in the art unit. Thus, inventions based on an optical integrated circuit, for example, are reviewed by a few examiners in a group associated with integrated optics.

The Patent Examiner reviews the application to ensure it complies with the statutory requirements. If the examiner identifies any noncompliance, the examiner will reject the application in an “office action,” a document explaining the reasons for rejecting the application. The four most common reasons for rejection include the following:

1. The claimed invention is “anticipated” by a prior art reference.

2. The claimed invention is “obvious” given one or more prior art references.

3. The claims are not supported sufficiently by the specification.

4. The claim language is vague.

As part of the examination process, the examiner reviews prior art in the subject area of the claimed invention. The term “prior art” covers patents and publications that came out before the application’s filing date. If the examiner decides that a single prior art reference teaches all the elements of an application claim, then that claim is said to be “anticipated.” In the figure above, the prior art would fall within the circle of the independent claim. A response to this type of rejection would typically include an argument that one or more of the claimed limitations are different from what is taught in the prior art reference or an amendment of the claim to include a limitation not taught in the reference.

The statute requires that an invention not only be new, but also not “obvious.” This policy is applied to avoid rewarding someone with a patent for only making a small or trivial change to something that already exists. How this works in practice is that the examiner finds a primary prior art reference that teaches almost all the claim limitations and a secondary reference that teaches the missing limitation or limitations and presents arguments as to why a “person of ordinary skill”2 would consider amending the teachings in the primary reference to include what is taught in the secondary reference.

A response to this type of rejection could be the following:

1. Explain why the references don’t teach all the elements of the claim.

2. Specify why a person of ordinary skill would not consider combining the teachings of the two references.

3. Add an amendment to the claim to include a limitation not taught in the references.

The inventor may be asked to help the patent attorney respond to an anticipation or “obviousness” rejection, for example, to help the attorney understand the prior art or to understand the invention better so that the attorney can develop arguments to include in the response to the Patent Office.

The patent statute requires the specification to include sufficient detail so that a person of ordinary skill can practice the claimed invention. The patent attorney must achieve a balance between including enough information to meet this requirement and not so much information that the application becomes overly large. For example, in an invention concerning a photonic integrated circuit formed in a silica substrate, there may be no need to extensively describe how the waveguides are made in the substrate since this process is well known. However, if the invention relied on achieving an unusually high refractive index contrast between the waveguide and the substrate, the application would require a more detailed explanation of how to form the waveguide with the high index contrast. The inventor can help the attorney decide what processes and components are well known and which require a more thorough explanation.

The patent law also requires that the application contain a written description of the invention. Everything that appears in a claim limitation must be described in the application and, if possible, shown in a figure. If, say, a claim covers a lens having an antireflection coating, then that coating must be described in the application, no matter how obvious the inclusion of the coating is.

Last, the claims cannot be written in a way that leaves them vague or indefinite. Any ambiguity in the claim language will result in a rejection, which is usually relatively easy for the patent attorney to take care of by amending the offending claim.

What to do if your patent is rejected

Say the Patent Office has rejected your application for one or more of the reasons discussed above, and the attorney has submitted a response, which may include amendments to one or more of the claims. If the examiner remains unhappy with the claims, the subsequent office action is “final.” This determination is not as bad as it sounds and merely means that you, the applicant, have fewer options for responding. If there are minor amendments available to make the application allowable, the applicant can enter such amendments. Alternatively, the applicant can appeal the examiner’s position if the applicant believes the examiner is wrong or can file a Request for Continuing Examination (RCE), which resets the examination from scratch. Of course, there is a fee involved with filing the RCE. However, it’s not uncommon to file several RCEs in complicated cases.

Once the examiner is satisfied that the application complies with the legal requirements, he or she issues a Notice of Allowance, at which point prosecution of the application ends. The applicant, then, only must pay an Issue Fee to have the allowed application granted as a patent.

I have highlighted several areas where close cooperation between the inventor and the patent attorney can result in a better application. Above all, don’t leave your patent attorney to guess what your invention is about. Please take the time to work through the invention together and explore different ways of achieving the same solution. The more applicable information in the specification, the more valuable the patent can be. If the patent becomes the subject of litigation, it will be reviewed forwards, backward, and sideways by attorneys looking for weaknesses. They will spend weeks analyzing every detail of the patent and the history of the application’s proceedings at the Patent Office. So, don’t skimp on giving your patent attorney a few hours to make your patent withstand such scrutiny.

REFERENCES

1. I use the term “patent attorney” here, but a patent application can also be prepared by a patent agent. Both patent attorneys and patent agents have passed the registration exam set by the U.S. Patent Office. In the U.S., a patent attorney is also a licensed lawyer. In other jurisdictions, such as countries affiliated with the European Patent Office, a patent attorney is registered to practice before the relevant patent office, but need not be a practicing lawyer.

2. A “person of skill in the art” is a fictional person who has normal, not expert, skills and knowledge in a technical field.

This article is the author’s opinion, not that of Laser Focus World or Carlson Caspers. The information presented here should not be relied upon as legal advice.

About the Author

Iain McIntyre

Iain A. McIntyre, J.D., Ph.D., is a partner at the Minneapolis law firm Carlson Caspers. He earned his doctorate in laser physics from The University of St. Andrews in Scotland. After working in lasers and electro-optics for 10 years, he switched careers and has worked in patent law for more than 25 years. He is experienced in patent prosecution, litigation, counseling, FTO, and due diligence analyses.