Research team discovers key feature of ion pump for optogenetics

An international team of researchers has developed a hypothesis to explain the function of a light-driven protein that pumps sodium ions across a cell membrane, and have revealed the key structural feature of these pumps. The scientists—from the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology (MIPT; Russia), Research Centre Jülich (Germany), the Max Planck Institute of Biophysics (Frankfurt, Germany), and the Institut de Biologie Structurale (Grenoble, France)—see these sodium pumps as being highly promising tools in using light signals to control nerve cells, which is what is involved in optogenetics.

Related: Light-driven ion pump may provide blueprint for optogenetics

One of the many applications in optogenetics is working with individual cells of the nervous system to study various types of neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s. Studies have also been conducted that demonstrate that optogenetic methods can be used to restore vision in mice. In the research team's study, they looked at the membrane protein KR2 that is found in cell membranes—when exposed to light, it is able to transport sodium ions.

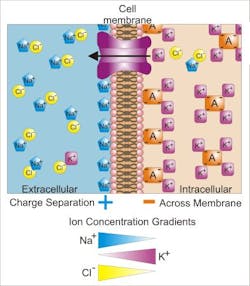

The research team built upon previous research to analyze the structure of the light-driven sodium pump KR2 in various states. They were then able to use this analysis to propose a model of the molecular function of this pump. When light hits the retinal (the light-driven element in the structure of a pump), it undergoes an isomerization (change in molecular arrangement) and allows a sodium ion to enter the protein. When the sodium enters the protein, the retinal changes again, preventing the sodium from going back in the direction from which it came. When the sodium is released again, the protein returns to its original state and is ready to absorb the next photon.

The scientists also analyzed how the pump function is affected by the fact that in a membrane, it often forms oligomers--groups of several proteins close to each other (the particular protein analyzed forms pentamers--a complex of five proteins). It was found that the width of the “gates” enabling an ion to pass through in the proteins in these complexes is slightly bigger than in monomeric KR2—12 Å compared to 10. In other pumps with known structures responsible for proton transfer, this distance can also be measured and it will be less than in KR2.

“We believe that the value of approximately 12 Å may be the minimum value for a protein to be able to transfer a charged ion instead of a proton. Knowing this threshold value, we can use computer methods to modify other pumps in this way so they transfer the ions we need. Of course, this will require further adjustments in a number of key places in the protein,” comments Vitaly Shevchenko, an author of the study and a researcher of MIPT’s Laboratory for Advanced Studies of Membrane Proteins.

The protein KR2 has the potential to become a key tool in optogenetics. Research in this field is also being conducted at MIPT and it was recently announced that a center would be established for aging and age-related diseases, which is also planned to include an optogenetics laboratory headed by Professor Valentin Gordeliy, the corresponding author of the study.

Full details of the work appear in the journal FEBS Letters; for more information, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/febs.13585.

Follow us on Twitter, 'like' us on Facebook, connect with us on Google+, and join our group on LinkedIn