Flow cytometry discovers bacteria that links Crohn's disease to joint pain

Using flow cytometry, which involves fluorescent probes for detection, a team of researchers from Weill Cornell Medicine (New York, NY) and colleagues has demonstrated the connection between Crohn's disease (an inflammatory bowel disease) and joint pain. The discovery could someday help physicians identify Crohn's disease patients who are more likely to develop spondyloarthritis (a painful condition that affects the spine and joints), enabling them to prescribe more effective therapies for both conditions.

Related: Flow cytometry helps provide biochemical clues to who develops Alzheimer's disease

The technique helped the researchers identify a type of Escherichia coli (E. coli) bacteria found in people with Crohn's disease that can trigger inflammation associated with spondyloarthritis, according to the study led by principal investigator Dr. Randy Longman, assistant professor of medicine and director of the Jill Roberts Institute Longman Lab at Weill Cornell Medicine, along with scientists from the Jill Roberts Center for Inflammatory Bowel Disease at New York-Presbyterian and Weill Cornell Medicine, the Jill Roberts Institute for Research in Inflammatory Bowel Disease at Weill Cornell Medicine, microbiologists at Cornell University, and rheumatologists at the Hospital for Special Surgery.

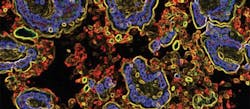

The researchers used fecal samples from patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) to identify bacteria in the gut that were coated with antibodies called immunoglobulin-A (IgA) that fight infection. Using flow cytometry, in which fluorescent probes are used to detect IgA-coated bacterial species, the researchers discovered that IgA-coated E. coli were abundant in fecal samples from patients with both Crohn's disease and spondyloarthritis. Using both patient samples and mouse models, they then linked these bacteria to cells that help regulate inflammation, known as Th17 cells, in people with autoimmune disorders.

The investigators found that patients with Crohn's disease and spondyloarthritis had higher levels of Th17 cells, and that a protein called IL-23 triggers their activity. With the recent FDA approval of an anti-IL-23 medication for Crohn's disease called ustekinumab, the findings may help physicians select therapies that target symptoms of both the bowels and joints in these patients, Longman says.

"Just sequencing the gut flora gives you an inventory of the bacteria, but does not tell you how they are perceived by the host immune system," says study co-author Dr. Kenneth Simpson, professor of small animal medicine at Cornell's College of Veterinary Medicine, whose laboratory characterized the E. coli identified in the study. "If we can block the ability of bacteria to induce inflammation, we may be able to kick Crohn's disease and spondyloarthritis into remission."

"In IBD therapy, this is a step toward precision medicine—to be able to clinically and biologically characterize a subtype of disease and then select the medicine that would best fit the patient with this type of inflammation," Longman adds. "The results of this innovative study will start to inform our decision of which of our available medications will give the best chance of helping the individual patient."

Full details of the work appear in the journal Science Translational Medicine; for more information, please visit http://stm.sciencemag.org/content/9/376/eaaf9655.