Novel post-op patch delivers drug, gene, and light therapy to tumor sites

Conventional therapies used to prevent tumors recurring after surgery do not sufficiently differentiate between healthy and cancerous cells, leading to serious side effects. Recognizing this, researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT; Cambridge, MA) developed an adhesive patch that can stick to the tumor site, either before or after surgery, to deliver a combination of drug, gene, and light therapy.

Related: Hydrogel bandage with embedded LEDs can deliver medicine to the skin

Releasing this combination therapy locally, at the tumor site, may increase the efficacy of the treatment, according to Natalie Artzi, a principal research scientist at MIT's Institute for Medical Engineering and Science (IMES) and an assistant professor of medicine at Brigham and Women's Hospital (Boston, MA), who led the research.

Currently, cancer treatment involves the use of systemic therapies such as chemotherapy drugs. But the lack of specificity of anticancer drugs means they produce undesired side effects when systemically administered. What's more, only a small portion of the drug reaches the tumor site itself, meaning the primary tumor is not treated as effectively as it should be. Recent research in mice has found that only 0.7% of nanoparticles administered systemically actually found their way to the target tumor.

So, the researchers developed a triple-therapy hydrogel patch, which can be used to treat tumors locally. This is particularly effective, as it can treat not only the tumor itself but any cells left at the site after surgery, preventing the cancer from recurring or metastasizing in the future.

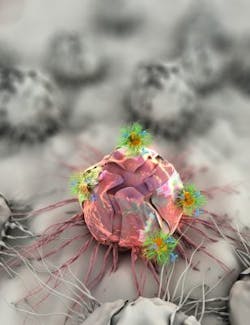

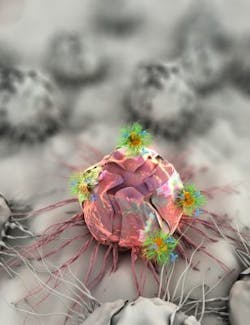

The patch contains gold nanorods, which heat up when near-infrared (NIR) radiation is applied to the local area. This is used to thermally destroy the tumor. These nanorods are also equipped with a chemotherapy drug, which is released when they are heated, to target the tumor and its surrounding cells. Finally, gold nanospheres that do not heat up in response to the NIR radiation are used to deliver RNA, or gene therapy to the site, to silence an important oncogene (a gene that can cause healthy cells to transform into tumor cells) in colorectal cancer.

The researchers envision that a clinician could remove the tumor, and then apply the patch to the inner surface of the colon, to ensure that no cells that are likely to cause cancer recurrence remain at the site. As the patch degrades, it will gradually release the various therapies. The patch can also serve as a neoadjuvant, a therapy designed to shrink tumors prior to their resection, Artzi says.

When the researchers tested the treatment in mice, they found that in 40% of cases where the patch was not applied after tumor removal, the cancer returned. But when the patch was applied after surgery, the treatment resulted in complete remission--even when the tumor was not removed, the triple-combination therapy alone was enough to destroy it.

Unlike existing colorectal cancer surgery, this treatment can also be applied in a minimally invasive manner. In the next phase of their work, the researchers hope to move to experiments in larger models to use colonoscopy equipment not only for cancer diagnosis, but also to inject the patch to the site of a tumor when detected.

"This administration modality would enable, at least in early-stage cancer patients, the avoidance of open field surgery and colon resection," Artzi says. "Local application of the triple therapy could thus improve patients' quality of life and therapeutic outcome."

Full details of the work appear in the journal Nature Materials; for more information, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nmat4707.