FEMTOSECOND LASER/CELL BIOLOGY: Ultrafast laser enables cell study, with big implications

A femtosecond laser has enabled researchers at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS; Cambridge, MA) to better understand cell division processes and dispel a widely held incorrect assumption. The ultrafast laser allowed the team to make precise cuts in cells and perform experiments that would not have otherwise been possible, says Eric Mazur, Balkanski Professor of Physics and Applied Physics at Harvard, who co-authored a study describing the work.1

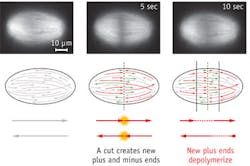

Mazur and colleagues used the laser to slice through and make quantitative measurements of the mitotic spindle (an apparatus that forms during cell division) in frog egg extracts, and discover how its microtubules (protein strands) are organized in the spindles of animal cells.

The spindle is the structure that segregates chromosomes into the daughter cells. It was previously unclear how microtubules are organized in the spindles of animal cells, and it was often assumed that they stretch along the length of the entire structure. The team demonstrated that the microtubules can begin to form throughout the spindle, and that they vary in length. "We wondered whether this size difference might result from a gradient of microtubule stabilization across the spindle, but it actually results from transport," says lead author Jan Brugués, a postdoctoral fellow at SEAS. The microtubules generally nucleate and grow from the center of the spindle, and move toward the poles. "They disassemble over the course of their lifespan, resulting in long, young microtubules close to the midline and older, short microtubules closer to the poles."

With further work, the researchers hope for a complete understanding, and possibly even control over, the formation of the spindle. Brugués says the discovery has left his team with "more hope of tackling the range of conditions—from cancer to birth defects—that result from disruptions to the cell cycle or from improper chromosomal segregation."

1. J. Brugués et al., Cell, 149, 3, 554–564 (2012).

More BioOptics World Current Issue Articles

More BioOptics World Archives Issue Articles