Label-free microscopy method could enable real-time diagnostics

Researchers at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign have developed a microscopy technique that can image living tissue in real time and in molecular detail, without any chemicals or dyes.

The technique, called simultaneous label-free autofluorescence multi-harmonic microscopy (SLAM), uses precisely tailored pulses of light to simultaneously image with multiple wavelengths. This enables study of concurrent processes within cells and tissue, and could give cancer researchers a new tool for tracking tumor progression and physicians new technology for tissue pathology and diagnostics.

Related: Ultrafast light-pulse method could control neuron activity

SLAM microscopy differs from standard tissue pathology in several ways. First, it is used on living tissue, even inside a living being, giving it the potential to be used for clinical diagnosis or to guide surgery in the operating room. Second, it uses no dyes or chemicals—only light. The lengthy standard procedure involves removing a tissue sample and adding chemical stains, and the chemicals can disrupt the cells.

While other stain-free imaging techniques have been developed, they usually only visualize a subset of signals, measuring specific biological or metabolic signatures, says graduate student Sixian You, the first author of the paper. Meanwhile, SLAM microscopy simultaneously collects multiple contrasts from cells and tissues, capturing molecular-level details and dynamics such as metabolism.

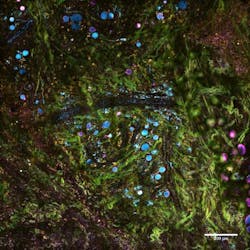

In the most recent study, led by Stephen Boppart, a professor of bioengineering and electrical and computer engineering and a medical doctor, the research team looked at mammary tumors in rats, along with the surrounding tissue environment. Thanks to the simultaneous data, they were able to observe the range of dynamics as the tumors progressed and how different processes interacted.

The researchers saw that the cells near the tumor had differences in metabolism and morphology, indicating that the cells had been recruited by the cancer. In addition, they observed surrounding tissues creating infrastructure to support the tumor, such as collagen and blood vessels. They also saw communication between the tumor cells and the surrounding cells in the form of vesicles, tiny transport packages released by cells and absorbed by other cells.

Next, Boppart’s group is using SLAM microscopy to compare healthy tissue and cancer tissue in both rats and humans, focusing particularly on vesicle activity and how it relates to cancer aggressiveness. They are also working to make portable versions of the SLAM microscope that could be used clinically.

Full details of the work appear in the journal Nature Communications.