Tissue-expansion technique maps brain circuits in super-res, and at low cost

Seeking a way to capture super-resolution microscopy images at low cost, researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT; Cambridge, MA) have developed a technique that relies on expanding tissue before imaging it with a conventional light microscope.

Related: Tissue sampling method could enable low-cost super-resolution microscopy

Building on their previous work showing that it was possible to expand tissue volumes 100-fold, resulting in an image resolution of about 60 nm, the research team has now shown that expanding the tissue a second time before imaging can boost the resolution to about 25 nm. This level of resolution allows scientists to see, for example, the proteins that cluster together in complex patterns at brain synapses, helping neurons to communicate with each other. It could also help researchers to map neural circuits, says Ed Boyden, an associate professor of biological engineering and brain and cognitive sciences at MIT.

"We want to be able to trace the wiring of complete brain circuits," says Boyden, the senior author of a new paper describing the work. "If you could reconstruct a complete brain circuit, maybe you could make a computational model of how it generates complex phenomena like decisions and emotions. Since you can map out the biomolecules that generate electrical pulses within cells and that exchange chemicals between cells, you could potentially model the dynamics of the brain."

This approach could also be used to image other phenomena such as the interactions between cancer cells and immune cells, to detect pathogens without expensive equipment, and to map the cell types of the body.

To expand tissue samples, the researchers embed them in a dense, evenly generated gel made of polyacrylate, a very absorbent material. Before the gel is formed, the researchers label the cell proteins they want to image, using antibodies that bind to specific targets. These antibodies bear barcodes made of DNA, which in turn are attached to cross-linking molecules that bind to the polymers that make up the expandable gel. The researchers then break down the proteins that normally hold the tissue together, allowing the DNA barcodes to expand away from each other as the gel swells.

The enlarged samples can then be labeled with fluorescent probes that bind the DNA barcodes, and imaged with commercially available confocal microscopes, whose resolution is usually limited to hundreds of nanometers. Using that approach, the researchers were previously able to achieve a resolution of about 60 nm. However, "individual biomolecules are much smaller than that, say 5 nm or even smaller," Boyden says. "The original versions of expansion microscopy were useful for many scientific questions, but couldn't equal the performance of the highest-resolution imaging methods such as electron microscopy."

In their original expansion microscopy study, the researchers found that they could expand the tissue more than 100-fold in volume by reducing the number of cross-linking molecules that hold the polymer in an orderly pattern. However, this made the tissue unstable—doing so, the polymers no longer retain their organization during the expansion process, so the information disappears, Boyden says.

Instead, in their latest study, the researchers modified their technique so that after the first tissue expansion, they can create a new gel that swells the tissue a second time—an approach they call "iterative expansion." With it, they were able to image tissues with a resolution of about 25 nm, which is similar to that achieved by super-resolution techniques such as stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM). However, expansion microscopy is much cheaper and simpler to perform because no specialized equipment or chemicals are required, Boyden says. The method is also much faster and thus compatible with large-scale, 3D imaging.

The resolution of expansion microscopy does not yet match that of scanning electron microscopy (about 5 nm) or transmission electron microscopy (about 1 nm). However, electron microscopes are very expensive and not widely available, and with those microscopes, it is difficult for researchers to label specific proteins.

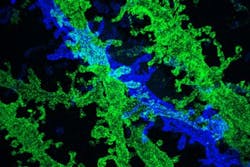

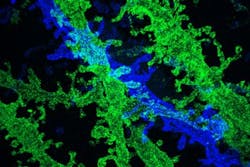

In the new paper, the MIT team used iterative expansion to image synapses—the connections between neurons that allow them to communicate with each other. In their original expansion microscopy study, the researchers were able to image scaffolding proteins, which help to organize the hundreds of other proteins found in synapses. With the new, enhanced resolution, the researchers were also able to see finer-scale structures, such as the location of neurotransmitter receptors located on the surfaces of the "postsynaptic" cells on the receiving side of the synapse. In the coming years, Boyden hopes to begin to map out the organization of these scaffolding and signaling proteins at the synapse.

Combining expansion microscopy with a new tool called temporal multiplexing should help to achieve that, Boyden says. Currently, only a limited number of colored probes can be used to image different molecules in a tissue sample. With temporal multiplexing, researchers can label one molecule with a fluorescent probe, take an image, and then wash the probe away. This can then be repeated many times, each time using the same colors to label different molecules. "By combining iterative expansion with temporal multiplexing, we could in principle have essentially infinite-color, nanoscale-resolution imaging over large 3D volumes," Boyden says.

The researchers also hope to achieve a third round of expansion, which they believe could enable resolution of about 5 nm. However, right now the resolution is limited by the size of the antibodies used to label molecules in the cell. These antibodies are about 10 to 20 nm long, so to get resolution below that, researchers would need to create smaller tags or expand the proteins away from each other first and then deliver the antibodies after expansion.

Full details of the work appear in the journal Nature Methods; for more information, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.4261.