Optical trapping method observes bacteria in super resolution without sample prep

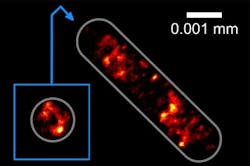

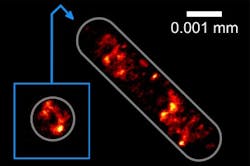

By using a method that traps biological cells with a laser beam for study under a microscope, a team of researchers at Bielefeld University (Germany) and colleagues is able to obtain super-resolution microscopy images of DNA in single bacteria. The method avoids the need for sample preparations, which can harm these types of cells under observation.

Related: Researchers develop open source software for high-resolution microscopy

Many bacteria and blood cells prefer to be able to swim freely in solution, as they are continuously in rapid flow and do not remain on surfaces. If they adhere to a surface, this changes their structure and they die. Thomas Huser, head of the Biomolecular Photonics Research Group in the Faculty of Physics at Bielefeld University, explains that the research team's method allows them to take these freely moving cells and then use an optical trap to study them at a very high resolution. The cells are held in place by a laser beam to not only immobilize them without a substrate, but can also turn and rotate them for study under a microscope.

The researchers have further developed the procedure for use in super-resolution microscopy by using a second laser beam as an optical trap so that the cells float under the microscope and can be moved at will. "The laser beam is very intensive, but invisible to the naked eye because it uses infrared light," says Robin Diekmann, a member of the Biomolecular Photonics Research Group. "When this laser beam is directed towards a cell, forces develop within the cell that hold it within the focus of the beam."

Using their new method, the physicists have succeeded in holding and rotating bacterial cells in such a way that they can obtain images of the cells from several sides. Thanks to the rotation, the researchers can study the three-dimensional structure of the DNA at a resolution of ~0.0001 mm.

Professor Huser and his team want to further modify the method so that it will enable them to observe the interplay between living cells. They would then be able to study, for example, how germs penetrate cells.

To develop the new methods, the scientists are working together with Mike Heilemann and Christoph Spahn from Johann Wolfgang Goethe University (Frankfurt, Germany).

Full details of the work appear in the journal Nature Communications; for more information, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ncomms13711.