Photoacoustic flow cytometry could allow early thrombosis detection

The Department of Biological and Medical Physics at the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology (MIPT; Russia) led a team of researchers from the University of Arkansas for Medical Science (UAMS; Little Rock, AR), University Hospital Frankfurt, and University Hospital Dresden (both in Germany) on a series of experiments on mice to detect thrombosis (blood clotting) using photoacoustic flow cytometry.

Related: The wide-ranging benefit of photoacoustic commercialization

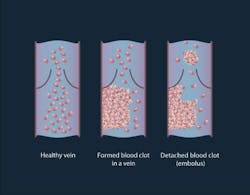

A thrombus formation is a healthy response to injury intended to prevent bleeding, but can be harmful in case of thrombosis, when clots obstruct blood flow through blood vessels. A thrombus lodging inside a blood vessel is called an embolus (an embolus may be a fat globule, a bubble of air, or another gas). Thromboembolism is the flow of a clot that breaks loose in the bloodstream to block another vessel. It is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality, especially in adults.

Existing methods do not provide accurate results and are not able to destroy thrombi. Doppler ultrasound techniques have shown promise for detecting a large thrombus in vivo, but this method cannot detect micro-thrombi, suffers from artifacts, and requires highly trained personnel. As a result, many thromboses remain undetectable: about 5–10% of patients die because of a failure to diagnose rather than inadequate therapy. Although the risk of recurrence decreases with longer durations of preventive anticoagulant treatment, there is no tool for estimating the risk of thrombus-related complications vs. the risk of bleeding-associated complications—particularly hemorrhage.

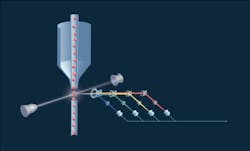

So, the research team used photoacoustic flow cytometry as a theranostics (a combination of diagnostics and therapy) approach. The method, which involves irradiating fluorescent dye-labeled cells with a laser beam, provides high spatial resolution for detecting signals up to a few millimeters and potentially destroying the blood clots. The specific wavelength excites fluorescent markers and they emit light at their own wavelength (which differs from the excitation wavelength). The emitted light is collected by a lens and mirror system and decomposed. The detected light is then converted into electrical impulses recognized by a computer, which analyzes the data and plots graphs. Peaks on the graph indicate the blood clot and its type. During the experiment, the mice were injected with a fluorescent dye and the laser was directed onto the blood vessels in their paws.

In this preclinical study, the scientists conducted experiments on two groups of mice: healthy and melanoma-bearing. In the group of healthy mice, either clamps were applied to their legs or an incision was made by cutting through the skin and muscle on the mouse's back. In both situations, emboli were produced. In the melanoma-bearing mouse model, researchers observed a correlation between the presence of white emboli and melanoma.

The signals obtained were first averaged 10 times to increase the signal-to-noise ratio, followed by tracing the peak-to-peak amplitude of waveforms. The appearance of a negative peak indicates the passage of a low absorbing object (e.g., white embolus). Traces were then analyzed for the presence of positive and negative peaks exceeding the thresholds obtained from a control experiment.

The method, says Alexander Melerzanov, Ph.D., dean of MIPT, could also be used to destroy blood clots, which is something that the research team is planning to work on in following experiments. The team, he says, expects that a clinical device using the method could be attached to a patient's hand, or bypass tubes in the operating room or during a transfusion procedure.

Full details of the work appear in the journal PLOS One; for more information, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0156269.