To find and count specific cells in a group of many different cells, researchers often turn to flow cytometry. Typically, this technology forces cells into single file and streams them by a detector. Beyond providing quantification, this process works fast—some instruments analyzing about 100,000 cells each second. To push this technology into more labs and broader applications, many academic and industrial researchers hope to simplify cytometry, while still getting more power from it.

At the University of California, Los Angeles, for example, Dino Di Carlo and his colleagues turned to microfluidics to enhance the throughput of a flow cytometer. They have created a 256-channel device that can crank through 28,000,000 cells a second. To distinguish cell types, this instrument uses an opto-electronic sensor chip-all without a single lens. (See the SPIE article, "Inertial focusing significantly enhances miniature flow-cytometry throughput.")

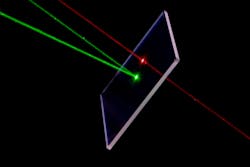

As this example shows, researchers place high expectations on current advances in cytometry. "Optical design on a flow cytometer involves tight tolerances due to the complex system interactions between lasers, filters, optics and detectors," says Yuri Sikorski, senior staff optical/mechanical engineer at Beckman Coulter's cellular analysis business group in Fort Collins, CO.

Making it modular

Practitioners in the field of flow cytometry are constantly testing the boundaries of the discipline, and some of the cutting-edge research requires configurability built into the design of the product. That is what Beckman Coulter seeks to provide with its new MoFlo Astrios product, and BD Biosciences (Franklin Lakes, NJ) aims for with its Influx cell sorter. In describing this instrument, Sikorski says, "It is highly modular and has an architecture that supports modularity in lasers, filters, detectors and so on."

Beyond the modularity provided, Sikorski points to the MoFlo Astrios' ease of use. "Optics on a typical flow cytometer typically requires someone with a Ph.D. in optics to understand the innards of the system," he says. The MoFlo Astrios addresses some of this complexity through its system design, resulting in a high-end, user-friendly platform that balances the need of beginners and experts in this exciting field. Sikorski adds, "On the MoFlo Astrios, we offer seven lasers and a gamut of supporting filters that cover a majority of the fluorophores in use."

Other flow cytometry systems vendors are also emphasizing ease of use, as well as low-cost and low-volume applications. (See "Cell Bio emphasizes easy access, low volume.")

Faster with fiber optics

Conventional spectrometry disperses color into space. That is, one diffraction grating can be used to separate colors that get analyzed with multiple detectors (pixels). On the other hand, says Gary Carver, director of research at Omega Optical (Brattleboro, VT), "We can use many diffraction gratings and one detector to disperse signals in time instead of space."

"Using multiple bulk diffraction gratings, though, is impractical," Carver says. To make this affordable, Omega Optical uses gratings inside optical fibers, fabricated by shining ultraviolet light on the fiber where the user wants a grating. As Carver points out, "You can make a series of gratings along the fiber in a pretty low-cost way." Each of these gratings can also be adjusted to a particular center wavelength.

This technology could be applied to cytometry. "People are doing cytometry at multiple wavelengths, and they would like to use more," Carver says. Indeed, Omega Optical has developed and sold filters to major cytometry researchers and original equipment manufacturers since the 1970s and '80s.

"We could take the fluorescence from a cell, pump it into a fiber and then distribute the light in time to examine more wavelengths than researchers currently have," Carver explains. "We could also do it very quickly with our technology." He adds, "We're imagining an arrangement where we build a subsystem with spectral elements that are applicable to a given disease or cytometric application."

Tracking more targets

When using flow cytometry, many biologists want to track more targets. While the technology could only track a few targets less than a decade ago, today's researchers envision tracking a couple dozen targets in the near future. By simultaneously following so many targets, biologists will be able to gather information that simply flowed away in the past.

Not surprisingly, companies that make products for flow cytometry understand the desire to track more. For example, the Life Technologies website states: "Higher-plexed multicolor flow cytometry reveals more information about each individual cell—in less time, with less sample." More targets can be tracked simultaneously with Life Technologies' Qdot nanocrystals, which provide narrow emission bands when excited by a laser. Moreover, these nanocrystals can be conjugated with antibodies to label specific targets on a cell.

To distinguish a growing list of markers, researchers will need advanced filters in some cases. For example, researchers who want to use coatings to make filters for cytometric applications demand increasingly sophisticated features: deeper and narrower notches, cleaner edges and so on. Meeting those demands requires coating companies to keep pace with the latest technology. For instance Ian Moyes, managing director at Artemis Optical Limited (Plympton, England), says, "we will be adding $1.2 million of next generation-coating technology, which will be delivered here around August 2011. It will give us the opportunity to make higher-quality, more-precise coatings and to do that repeatedly."So, advanced filters, fiber-optic approaches, microfluidics and more will give tomorrow's biologists more opportunities to study cells with cytometry. In addition, researchers will track more cells, do it faster and study more characteristics.

About the Author

Mike May

Contributing Editor, BioOptics World

Mike May writes about instrumentation design and application for BioOptics World. He earned his Ph.D. in neurobiology and behavior from Cornell University and is a member of Sigma Xi: The Scientific Research Society. He has written two books and scores of articles in the field of biomedicine.