INTERFEROMETRY: Fluorescence-based interferometer halves fringe spacing

Two scientists at the Université Joseph Fourier (Saint Martin d’Hères, France) have developed an extraordinary interferometer. Based on the effects of polarized laser light on a hot vapor of sodium atoms, the interferometer creates a fringe for every relative phase change of λ/2 (half wavelength), as opposed to all other interferometers ever made, which create a fringe for every λ (full wavelength) relative phase change.1 (Note that an ordinary distance-measuring interferometer produces one fringe count for every shift of its movable mirror by λ/2; however, this is merely due to the fact that the reflection results in a change in optical path length twice that of the actual mirror displacement. If a distance-measuring interferometer were to be made using the new technique, it would produce a fringe count for every λ/4 mirror displacement.)

Varying polarization

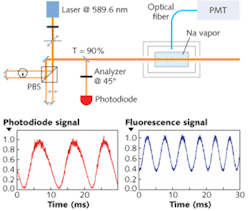

A beam from a dye laser produces light at the sodium line at 589.6 nm, but with a bandwidth broad enough to cover the entire Doppler-hyperfine width; the laser has an intracavity acousto-optic frequency shifter that prevents the usual cavity interferences from occurring. The laser beam is linearly polarized at 45° and split into two orthogonally polarized beams, one for the stationary interferometer arm and one for the phase-shifted arm. When the beams are recombined, the resulting beam varies from linear to elliptical to circular polarization, depending on the amount of phase shift between the interferometer arms.

The resulting beam is then passed through the excited sodium vapor. When the beam is linearly polarized, it induces absorption fluorescence in the vapor; however, when the beam approaches circular polarization, it pumps the sodium into a dark state, causing a λ/2 fringe spacing in the fluorescence signal. The fluorescence signal is captured by an optical fiber leading to a photomultiplier tube (PMT), while at the same time the beat signal of the laser beam itself (the ordinary interferometer signal) is measured by a photodiode. (see figure). Although the fluorescence signal does show some continuous background, this could be reduced by using a wax-coated vapor cell, which would better preserve the atomic state when the sodium collides with the cell walls.

Not only is the interferometer twice as sensitive as a conventional instrument; in the saturation regime, the fluorescence fringes are expected to become very narrow, allowing their centers to be precisely located. The researchers foresee applications for their instrument in nanoscale displacement measurement and atom localization.

REFERENCE

- H. Guillet de Chatellus and J.P. Pique, Optics Letters 34(6) (March 15, 2009).

About the Author

John Wallace

Senior Technical Editor (1998-2022)

John Wallace was with Laser Focus World for nearly 25 years, retiring in late June 2022. He obtained a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering and physics at Rutgers University and a master's in optical engineering at the University of Rochester. Before becoming an editor, John worked as an engineer at RCA, Exxon, Eastman Kodak, and GCA Corporation.