Two lasers mix to create 11 different frequencies of light

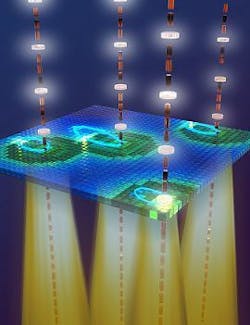

Santa Barbara, CA--By aiming two lasers—high- and low-frequency beams—at a semiconductor, a team of physicists at the University of California Santa Barbara (UC Santa Barbara or UCSB) have created multiple frequencies of light. The mixing process causes electrons to be ripped from their cores, accelerated, and then smashed back into the cores they left behind, a recollision that produces multiple light frequencies at the same time, as described in the journal Nature.

"This is a very remarkable phenomenon. I have never seen anything like this before," said Mark Sherwin, whose research group made the groundbreaking discovery. Sherwin is a professor of physics at UCSB and a co-author of the paper. He is also director of the campus's Institute for Terahertz Science and Technology.

When the high-frequency optical laser beam hits the semiconductor material—in this case, gallium arsenide nanostructures—it creates an electron-hole pair called an exciton. The electron is negatively charged, and the hole is positively charged, and the two are bound together by their mutual attraction. "The high-frequency laser creates electrons and holes," Sherwin explained. "The very strong, low-frequency free electron laser beam rips the electron away from the hole and accelerates it. As the low-frequency field oscillates, it causes the electron to come careening back to the hole." The electron has excess energy because it has been accelerated, and when it slams back into the hole, the recombined electron-hole pair emits photons at new frequencies. "It's fairly routine to mix the lasers and get one or two new frequencies, Sherwin continued. “But to see all these different new frequencies, up to 11 in our experiment, is the exciting phenomenon."

In terms of real-world applications, the electron-hole recollision phenomenon has the potential to significantly increase the speed of data transfer and communication processes. One possible application involves multiplexing—the ability to send data down multiple channels--and another is high-speed modulation.

The researchers utilize a free electron laser—a building-size machine in UCSB's Broida Hall—to produce the electron-hole recollisions, which they note is not practical for real-world applications. Theoretically, however, a transistor could be used in place of the free electron laser to produce the strong terahertz fields. "The transistor would then modulate the near infrared beam," Zaks continued. "Our data indicates that we are modulating the near infrared laser at twice the terahertz frequency. This is where we could really see this working to increase the speed of optical modulation, which is how you get information down a cable line."

Also contributing to the research is the paper's second author, R.B. Liu of The Chinese University in Hong Kong. "This is an excellent example of the value of communicating with scientists from all over the globe," said Sherwin. "If we had never met, this research would not have happened."

SOURCE: UC Santa Barbara; www.ia.ucsb.edu/pa/display.aspx?pkey=2679#description

About the Author

Gail Overton

Senior Editor (2004-2020)

Gail has more than 30 years of engineering, marketing, product management, and editorial experience in the photonics and optical communications industry. Before joining the staff at Laser Focus World in 2004, she held many product management and product marketing roles in the fiber-optics industry, most notably at Hughes (El Segundo, CA), GTE Labs (Waltham, MA), Corning (Corning, NY), Photon Kinetics (Beaverton, OR), and Newport Corporation (Irvine, CA). During her marketing career, Gail published articles in WDM Solutions and Sensors magazine and traveled internationally to conduct product and sales training. Gail received her BS degree in physics, with an emphasis in optics, from San Diego State University in San Diego, CA in May 1986.