Micromachining based on ultrafast laser pulses removes material by ablation with little or no heating of the neighboring area, reducing surrounding damage. Just as in ordinary laser machining, however, spatial nonuniformities in the ultrafast pulse as well as in material properties lead to uneven ablation and thus irregular depth. Researchers at the University of Aarhus (Aarhus, Denmark) are exploiting the brevity of femtosecond pulses to measure the depth profile of an ultrafast-micromachined area using the same pulses that are shaping it.1 The method lends itself to feedback techniques that can even out depth while a part is being machined.

By using an optical gate to measure the time of flight of light coming back from the part, the image of an object at a certain depth is acquired. The optical gate consists of a nonlinear crystal and is based on sum-frequency mixing. Inside the crystal, laser light received from the object is combined with a reference pulse coming directly from the ultrafast laser itself. Noncollinear phase matching eliminates the background from each of the two beams. The researchers note that other gating techniques could be used instead.

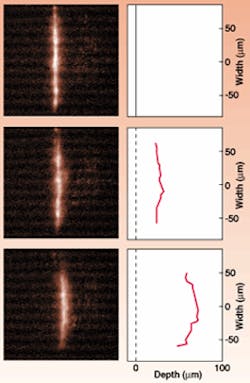

Femtosecond pulses lead to high depth resolution. In the experiment, an amplified Ti:sapphire laser emits 800-nm, 100-fs pulses at a 1-kHz repetition rate. Images taken of a stainless-steel plate during machining using these pulses shows a smear of about 20 µm (see figure). The smear results from a combination of surface debris left from machining and the duration of the pulse itself, the latter of which contributes approximately 15 µm to the smear. The images are obtained at a video rate.

As for feedback control, the simplest use of the depth information is as a signal to stop the machining of a hole at a preset depth. In another potential use, both lateral and depth dimensions of a hole can be kept to predetermined amounts by adjusting the position of a focusing lens. A third use has to do with laser milling, or translation of the part in a direction perpendicular to the laser beam. Here, the depth of the resulting trench can be kept within tight tolerances; alternatively, an uneven sample can be leveled. "One can use a laser beam spot smaller than the area to be made flat, and in a repetitive milling process adjust the scan rate or the pulse repetition rate based on the feedback signal," explains Peter Balling, one of the researchers. Such techniques also can be applied to laser eye surgery using ultrafast pulses.

REFERENCE

- R. Lausten and P. Balling, Appl. Phys. Lett. 79, 884 (Aug. 6, 2001).

About the Author

John Wallace

Senior Technical Editor (1998-2022)

John Wallace was with Laser Focus World for nearly 25 years, retiring in late June 2022. He obtained a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering and physics at Rutgers University and a master's in optical engineering at the University of Rochester. Before becoming an editor, John worked as an engineer at RCA, Exxon, Eastman Kodak, and GCA Corporation.