Much research on photonic devices for light-based silicon (Si) integrated circuits centers on the 1.5-µm telecommunications wavelength region; this past year, the advent of Si lasers and high-speed modulators has been the result (see p. 105). But another approach—the integration of non-Si semiconductors onto Si substrates—promises a wider range of wavelengths for many practical uses, including some beyond the optical transport of information. A group at the University of Cincinnati Nanoelectronics Laboratory (Nanolab; Cincinnati, OH) has developed the first of what will likely be a family of rare-earth (RE)-doped gallium nitride (GaN) coherent light emitters, most of which lase in the very important visible spectrum.1 The lasers are fabricated on Si and are potentially compatible with Si CMOS fabrication techniques. (The Nanolab group has also fabricated similar lasers from doped GaN grown on sapphire substrates.2)

The first device consists of an active 0.5-µm-thick GaN planar-waveguide layer doped with 1% europium (Eu) that is clad with a layer of aluminum gallium nitride (AlGaN). These layers were deposited onto a (111) Si substrate that already held several layers of GaN and AlGaN as a buffer, strain reliever, and bottom cladding. The substrate and layers were then cut and the ends polished to form a 350-µm-long planar laser cavity.

When the Nanolab researchers optically pumped the laser with 337-nm light from a pulsed nitrogen laser, they observed gain that saturated at about 95 cm-1 for an 8-MW/cm2 pump intensity; the pump threshold was determined to be 117 kW/cm2. The emission was polarized, with a spectrum that peaked at 620 nm and revealed several longitudinal modes spaced apart by 0.4 nm; each mode had a linewidth (full width at half maximum) of 0.2 nm.

“The next step is to make a channel waveguide cavity,” says Andrew Steckl, one of the researchers. “We have obtained preliminary results that indicate that significant increases in gain will result.” The real challenge, notes Steckl, is to electrically pump the device. “We hope to be able to inject sufficient charge density in a p-i-n structure to generate the necessary density of excited rare-earth ions for stimulated emission,” he says.

One of the attractive features of the Nanolab approach, notes Steckl, is that there are so many colors available with various rare earths. Other rare-earth dopants besides europium include thulium, which emits in the blue (477 nm); erbium, which produces green (537 to 559 nm) and IR (1.5 µm); gadolinium, which emits in the UV (300 nm; gadolinium would require an AlGaN host); and others.

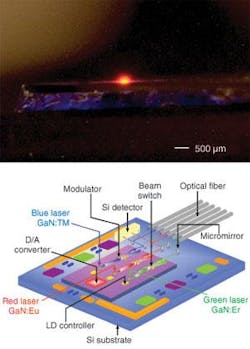

The growth process for the doped GaN-on-Si lasers is CMOS-compatible, says Steckl; the fabrication temperatures are relatively low (700°C to 800°C) and can be pushed lower with additional investigation. “Our vision is that you could integrate multiple sources on a single Si chip and control the output with built-in Si electronics,” he says. Such a device could include modulators, photodetectors, and light routers (see figure).

Steckl sees many potential applications of the rare-earth-doped GaN-on-Si technology, including displays (very pure red, green, and blue colors can be emitted); computing (optical interconnects for increasing the communication speed of chip-to-chip, processor to peripherals, and so on); low-cost on-chip spectroscopy; and low-cost discrete laser sources with a rainbow of colors (can combine rare-earth dopants in one device and generate a variety of colors).

REFERENCES

1. J.H. Park and A.J. Steckl, J. Applied Physics98, 056108 (2005).

2. J.H. Park and A.J. Steckl, Appl. Phys. Lett.85(20) (Nov. 15, 2005).

About the Author

John Wallace

Senior Technical Editor (1998-2022)

John Wallace was with Laser Focus World for nearly 25 years, retiring in late June 2022. He obtained a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering and physics at Rutgers University and a master's in optical engineering at the University of Rochester. Before becoming an editor, John worked as an engineer at RCA, Exxon, Eastman Kodak, and GCA Corporation.