Marketwatch: Think globally, cluster locally

W. Conard Holton,Executive Editor

Why do industries in certain geographic regions prosper while others struggle? How is it that some regionsfamously Silicon Valley and Hollywoodfoster a mix of workers, capital, infrastructure, and business acumen to become world leaders in an industry? "Clusters" is the answer, according to some economistsand agreeing with them more and more are business leaders interested in fostering success in the US optics industry.

The economist most associated with the cluster concept is Michael Porter, the C. Roland Christensen Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School (Boston, MA). Through his books and journal articles, Porter has convinced many influential people to see the world in terms of clusters: geographic concentrations of linked firms, suppliers, related industries, and specialized institutions that occur in a particular field and can achieve unusual competitive success.

As he writes in "Clusters and the new economics of competition" (Harvard Business Review, Nov.-Dec. 1998, p. 77), "Clusters are not unique; they are highly typicaland therein lies a paradox: the enduring competitive advantages in a global economy lie increasingly in local thingsknowledge, relationships, motivationthat distant rivals cannot match." He goes on to emphasize that clusters affect competition positively by increasing the productivity of all companies, driving the direction and pace of innovation, and encouraging new businesses, which further strengthen the cluster.

Echoing these thoughts on an international scale, The Competitiveness Institute was formed, with members drawn from the United Nations International Development Organization, World Bank, and many universities and national governments. Its mission is to improve living standards and local competitiveness of regions across the world by enhancing cluster-based development initiatives.

In the real world

Whereas Porter looks at clusters with the cool eye of an academic, many leaders in the optics industry take a more sanguine approach. Most notable among these leaders is Robert Breault, president of Breault Research Organization (Tucson, AZ) and chairman of the Arizona Optics Industry Association (AOIA). Breault has traveled the world urging the creation of optics clusters wherever a critical mass may exist.

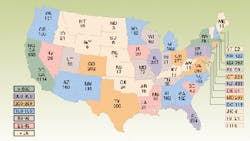

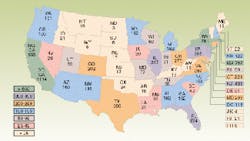

RIGHT. The distribution of optics-related companies in the USA, as compiled by SPIEThe International Society for Optical Engineering (Bellingham, WA) in May 1998, is a virtual match for the distribution of established or potential optics clusters.

"We're talking about a structured cluster concept," says Breault. And by that he means one where the basic ingredients of a cluster exist in terms of businesses and demand, but where close attention must be paid to matters of financing, infrastructure development, education, and the like. In the case of the Tucson area, a concerted effort led by the private sector and supported by the state government was launched in the late 1980s, when the Arizona economy came apart amid corporate downsizing and defense cutbacks. A state-wide strategy for economic development was devised, and the governor set up an organization to work closely with industry. Optics was seen as one of the ten existing clusters in Arizona that should be supported, and forming an association was seen as one way to strengthen it.

With nearly 200 member companies, the AOIA has the largest membership of any cluster-related association. And here it is worth noting that the terms "cluster" and "association" are sometimes used interchangeablyalthough they are different, they are also intertwined. A regional optics industry association may represent a few or many companies in a cluster, which is itself the combined organization of the association, the regional companies, the public sector, and the education system. The cluster is the focus of government support and of industry and academic cooperation. The needs and benefits of clusters are much broader than what is traditionally addressed by national associations, which are devoted to professional betterment or lobbying. The focus of a cluster and its association is business.

Most associations, including the one in the Tucson area, adhere to Breault's 50-mile rule, which states that members need to live within a convenient driving distance of each other to attend meetings and generally network. The majority of members are small to midsize companies, which are the ones that seem to benefit most from participation in a cluster. Larger companies are usually interested to the extent that their products involve optics, which in the case of Intel in the Tucson area is growing.

Breault lists the many optics-related clusters that are now organized or are "naturals" for future organization. Their locations clearly parallel the density of optics-related companies in the country (see map on p. 77). Formal associations now exist in Arizona, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Massachusetts, New Mexico, Pennsylvania, and New York. "Naturals," according to Breault, include northern and southern California, Illinois, Minnesota, New Jersey, and Texas. In Canada, clusters have been organized in southern Ontario, Ottawa, Quebec City, and Vancouver, while Montreal is a "natural." In the UK, Scotland and Wales each have an association. A look at some of these organized clusters reveals that each is different in history, structure, and degree of participation, yet finds a common vision in the term cluster.

East Coast groupings

Like Arizona, Connecticut has a government policy of promoting clusters, with a office devoted to their nurturing. In the early 1990s, DARPA provided the cluster a start with seed money to encourage strategic alliances between optics companies. More recently, the state has made $5 million available to support clusters, although it has not yet been released to support the optics cluster. Meanwhile, the cluster's official Connecticut Photonics Industry Association is being organized, with a recent meeting drawing up to 80 participants. There are more than 200 optics companies in the state.

Chandra Roychoudhuri, director of the Photonics Research Center at the University of Connecticut (Storrs, CT), is helping lead the effort. "Clusters enable small companies to behave like big, virtual companies," he says. "The optics companies have been here for a long time. It's only lately that [the government and other organizations] have come along to help support themit's important to provide these companies with the 'nourishment' they need to flourish."

Neighboring Massachusetts, with almost 800 optics companies, has the largest industry outside of California, which may help explain its low interest in additional organizing. The state has a cluster-based association, the Massachusetts Association for Optical Industry (MAOI), which is still forming and receives little active government support. It also has several other optics-related associations and a very diverse and prosperous industry, all of which leads MAOI member Groot Gregory, vice president at Lambda Research Corp. (Littleton, MA), to say that Massachusetts is not suffering from the same problems as other regions. In fact, he says, a extensive networking structure already exists and so the idea of pushing one big association to embrace the variety of companies in the region does not appeal to many managers. A similar situation in California has slowed the development of structured clusters.

A fellow high-density optics stateNew Yorkis still struggling with deep-seated economic problems and thus is potentially fertile ground for a structured cluster. Actually, it's fertile ground for several clusters given the distanceboth in miles and culturebetween the New York City/Long Island region and upstate New York. Bud Hippisley, principal of Cohasset Enterprises (Verona, NY), is executive director of the Photonics Industry Association of New York (PIANY) and has been working to make the 30-member association an umbrella group to foster more local clusters and provide a communication vehicle. PIANY has attracted considerable political interest and some funding from the state government.

Based on initial contacts, Hippisley thinks there is interest in forming associations in New York City/Long Island and the Utica/Rome regions. The Rochester Regional Photonics Cluster already has been incorporated, according to Chris Cotton of ASE Optics (Honeoye Falls, NY), secretary of the cluster. He says that the county and city governments are now interested and that the association wants to build a solid base of small to midsize companies.

In the West and beyond

The Colorado Photonics Industrial Association (CPIA) represents a region containing approximately 200 companies concentrated in the fast-growing front range of the Rockies between Colorado Springs and Fort Collins. Two-thirds of the optics companies, along with two universities and three national laboratories, are located near Boulder, according to CPIA secretary Brian Hooker, a professor of electrical engineering at the University of Colorado (Boulder, CO).

Hooker depicts the 50-member CPIA as a grass-roots organization formed by people who recognized the value of getting together. The group has only recently attracted a modest state grant of $30,000, although the state is involved in supporting the local optics industry through a $4.5 million investment in the Colorado Advanced Photonics Technology Center (on the former Lowry AFB), which serves as a common focus for education, testing, and prototyping.

Each region seems to be evolving its cluster in a different way. Some can afford a paid staff, some work closely with governments and universities, some create a common exhibit for trade shows, and some do none of these but rather continue an unofficial network that dates back to a common employer or graduate school. Amidst this growth, clusters are vulnerable, warns Michael Porter, not only to threats from competing clusters, but to internal threats brought on by overconsolidation, groupthink, regulatory inflexibility, stagnant schools, or any rigidity that undermines competition.

Despite the perils, believers such as Robert Breault assert that companies able to look past their local competitive instincts, mistrusts, and suspicions will find that proactive regional clusters will give them a deep competitive advantage and allow them to better weather such challenges as the increasing shortage of skilled labor. Breault says, "My job is to stitch together a network of optics clusters that know how to both cooperate and compete with each otherand do so on a national and international arena."