Optical scientists explore links to societal priorities

The unifying physics that allows optical scientists and engineers to understand each other at interdisciplinary scientific meetings differs significantly from the widely varying applications that interest potential funding agencies for optical research and development, according to John H. Marburger III, science advisor to the president and director of the U.S. Office of Science and Technology Policy (Washington, D.C.). He delivered his comments during the opening plenary address at the Optical Society of America's annual meeting (Oct. 5–9, Tucson, AZ).

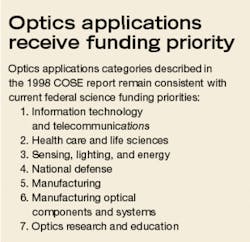

The roots of the optical "tree" lie in the electroweak theory that unifies the descriptions of electromagnetic and weak interactions, he said. The branches of the tree, however, are best described by the seven applications categories laid out in the 1998 report of the Committee on Optical Science and Engineering (COSE) of the National Research Council (see sidebar).1

"Many have heard of the COSE report but few have read it," Marburger quipped. He described the COSE report, however, as the best single source of how optics pervades technology today. "If you ever find yourself on a committee with such responsibilities [funding optics research], you might read this report because it lays out perspectives and vehicles useful for getting funding."

Making the connection

Funding agencies and society at large have shown a great deal of interest in the application areas laid out in the COSE report. But nonscientists are generally not interested in the electroweak interactions that provide a common ground for optics research along with the photons that actually enable both research and applications, he said. So it's up to optical scientists and engineers to make the connection.

"Science priorities should be based on science opportunities as well as social needs, because there is no logical connection between science needs and social needs," he said. "We are fortunate to live in a time and society in which there are coincidences between the two, and optical science and technology has the best of both worlds."

Nevertheless, people, tools, and ideas are the genesis of science, and we have to invest in these apart from social needs if we want to grow (scientifically), he added. When asked during the question-and-answer period what types of activities by individuals might help these efforts, Marburger emphasized the need to work through optics organizations such as the OSA to present a coherent voice rather than launching separate and potentially conflicting lobbying efforts. He also emphasized the need for optics education for the general public, as well as improved science and technology education in the lower grade levels. "We also need to address the dropout rate of people who go into universities to study science and are turned off in the first year."

Improving science education within the United States is important to maintain competitiveness and standard of living, he said. "But we also want to maintain the international flow of bright young people in science who have very much benefited U.S. science for the last six decades." So another important area of work has been to help solve student visa problems caused by security concerns (see figure). "It might be another year or more before it starts getting as efficient as you might like, but it is getting a lot of attention," he said.

REFERENCE

- Harnessing Light: Optical Science and Engineering for the 21st Century. National Academy Press, Washington, D.C. (1998).