Lasers shed light on Stonehenge secrets

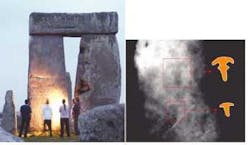

Two British archaeology ventures are using three-dimensional (3-D) laser scanning to discover and illuminate eroded stone etchings at Stonehenge (Wiltshire, England; see figure, left). Working with a low-power laser rangefinder and an imaging method known as laser triangulation, a team of scientists from Wessex Archaeology (Salisbury, England) and Archaeoptics (Glasgow, Scotland) have imaged carvings of two bronze axe heads that are not visible to the naked eye (see figure, right).

Carvings of axes and a dagger were first found at Stonehenge 50 years ago, but they have never been fully surveyed or studied. The team scanned some of these known carvings and by visually comparing their results with a photograph taken in 1953 they suspect the carvings may have eroded since they were first found, possibly because of people touching them. The stones at Stonehenge were put up in about 2300 B.C. The axe carvings are of types made around 1800 B.C., so the carvings are likely to be five centuries younger than the stones. The team scanned only a portion of three of the sarsen stones (sarsen are large sandstone blocks scattered across the English chalk downs) and believe that a full scan of all the surviving 83 stones would reveal more ancient carvings.

"The laser scanning has opened up a whole new way of seeing Stonehenge," said Tom Goskar of Wessex Archaeology. "We spent an hour recording the data at the stones and we were astounded to discover two new carvings as a result. With more time we could uncover many more and make plainer the outlines of some known carvings that are difficult to see."

Archaeoptics used a scanner made by Minolta (Tokyo, Japan) that is capable of capturing 300,000 image data points in three seconds. The tripod-mounted system operates at 690 nm and provides a maximum resolution of 170 µm.

To fully record a complex object such as the megaliths at Stonehenge, the scanner is manually moved around the object to measure points from many different angles, similar to photographing a stone from different sides to achieve complete coverage. At Stonehenge they acquired 9 million 3-D points on the stones in 30 minutes. They then took two days to create 3-D models from these points.

The raw data captured by the scanner are in the form of "point clouds"—unconnected points scattered three-dimensionally. To be more useful for visualization and analysis, these were converted into "solid" surfaces formed from millions of triangles. The models were then manipulated in a software package called Demon developed by Archaeoptics. Various lighting techniques were developed at Wessex Archaeology to further enhance the images.

"We have used 3-D scanning previously to enhance badly weathered carvings on monuments, but never on details as fine as the Stonehenge axeheads," said Alistair Carty, managing director at Archaeoptics. "The possibility that other unknown carvings exist on the other stones is very exciting and may hopefully lead to a more complete interpretation of Stonehenge."

According to Carty, Archaeoptics has used this same technology to image everything from machine parts to other artifacts, including the so-called "Seahenge," a Bronze Age timber circle found on a beach in Norfolk, England. The digital scans obtained by Archaeoptics at the Seahenge site provided much more detailed views of cut marks left on the timbers by at least 38 different bronze axes at a time when bronze technology had only recently come into Britain. They are the earliest metal tool marks on wood ever discovered in Britain.