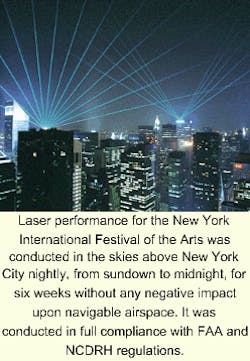

After five years of sometimes contentious debate, the aviation industry, the laser industry, and the federal government appear to be resolving many of their differences regarding laser displays and other outdoor laser uses that might inadvertently interfere with the eyesight of airplane pilots (see photo). Although at one point it seemed possible that outdoor laser displays might be banned altogether for fear that pilots might be flash-blinded by the displays, lengthy negotiation and discussion among industry representatives has produced a set of rules, standards, and procedures to govern use of the lasers. As a result, laser light shows will be allowed to proceed under circumstances that will minimize the possibility that they could trigger an airliner crash.

Most recently, in July the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced that officials from both agencies had signed a memorandum of understanding regarding the use of lasers in areas through which planes might fly. Under the agreement, the organizer of an outdoor light show must seek permission from the FDA. Before ruling, the FDA will check with the FAA, which will evaluate whether the light show will illuminate such areas.

The agreement also calls for the two agencies to jointly develop a system for collecting reports of incidents in which airplanes have been illuminated by lasers. The agencies agreed to work together in investigating the incidents and to share information—including proprietary data from companies—that each agency collects during an investigation.

A real issue

The issue of laser illumination of aircraft is not hypothetical, says C. W. "Bill" Connor, a retired Delta Air Lines captain and chairman of several key committees that have been working on aspects of the issue. Laser illumination first erupted as an aviation safety issue in 1995, when several Las Vegas, NV, hotels started outdoor laser shows near the airport, he said. "They were actually being projected into navigable airspace," said Connor, chairman of the laser-hazards-safety team of the Air Line Pilots Association (Herndon VA).

In one incident, the captain of an airliner had to turn control of his aircraft over to the copilot after the captain's eyes were illuminated by a ground-based laser. Although the captain suffered no permanent damage, at the time his vision was temporarily impaired. "He didn't know how long it would be before he could see," he said. Moreover, the captain was not even able to tell, using the balance mechanism from his inner ear, whether the plane was flying right side up because of the continuous turn that the plane was executing at the time. If both pilots had been illuminated by the laser and neither had been able to discern whether or not the plane was upside down, a serious accident could have resulted, said Connor. "Flash blinding is a very disruptive thing on the flight deck," said Connor. "The eyes are so critical."

In a year and a half of keeping track, pilots counted 51 incidents of laser illumination of aircraft near Las Vegas and began to demand a ban on the laser shows. Spurred by such statistics, the FAA asked the Society for Automotive Engineers (SAE)—which often plays a key advisory role for the agency—for advice on safety standards for laser shows. The SAE's G-10T subcommittee on laser hazards, which Connor also chairs, exhaustively researched the problem, drafting an advisory circular at the FAA's request that provides information to laser-display operators and proposed rules and regulations to govern their use. For example, Connor said, the committee developed standards for outdoor laser operations and for measuring the intensity of laser light in the airspace, as well as a map that specifies the allowable levels of laser light in various locations around an airport.

The committee and the laser-display industry found much to applaud in the document. For example, the industry convinced the G-10T committee to propose a prohibition on pilots who intentionally fly their planes into laser beams. The laser light show at the Walt Disney World Epcot Center in Florida has to be shut down 600 times every month when pilots fly into the area of the show, which they should well know about, said Patrick Murphy, airspace issues coordinator for the International Laser Display Association (Bradenton, FL).

Other good news for the industry in the G-10T report includes a recommendation that producers of laser shows continue to be allowed to use spotters to look for incoming aircraft that might be exposed to the lasers and a determination that the laser display industry should not be held to a stricter standard than other outdoor users of lasers, such as researchers.

Other hazards

Connor said that he has come to recognize that research lasers also can be a hazard to aircraft pilots if improperly operated. For example, he cited research by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (Livermore, CA) in using a laser to detect turbulence in the atmosphere as part of an adaptive-optics telescope that compensates for that turbulence and produces a sharper image than an ordinary ground-based telescope would generate. Such lasers are far more powerful than the ones used in laser light shows, Connor said.

Another growing concern, he said, is the wide availability of inexpensive laser pointers. Street gangs in Los Angeles, CA, have already tried to use sets of laser pointers to interfere with police helicopters, and a Boeing 727 on the tarmac at Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport had to return to the gate after someone illuminated the copilot with a laser pointer from a parking lot, Connor said.

The International Civil Aviation Organization has inquired about using the G-10T report as the basis of international standards on laser safety, Connor said. He welcomes that move. "Hopefully, we'll have a seamless safety net. No matter where pilots fly, they will have a base level of protection," he added.

And the ILDA's Murphy said that the laser display industry welcomes restrictions that will bolster aviation safety. "We don't mind if we have to do a little bit more work to prove that our shows are safe," he said.