Degradation of pigments in rare manuscripts is a significant problem for people dedicated to understanding the past. Conserving these irreplaceable documents requires nondestructive analytical techniques used in situ to identify the original pigments and determine how the damage has occurred and what can be done to reverse it. At the request of the British Library (London, England), scientists at University College London have achieved this goal with Raman microscopy.

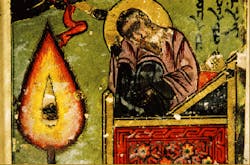

Robin Clark and Peter Gibbs of the university's chemistry department analyzed a 13th-century Byzantine gospel lectionary—a book of lessons from the Bible—containing 60 illustrations and valued at more than $1 million. The Byzantine Empire had its capital at what is now Istanbul in modern Turkey; it lasted from the 4th century AD until its conquest by the Turks in 1453. This manuscript is one of only two of similar age and style in existence and was clearly the property of an important person (see photo).

The value of the manuscript is threatened by the serious deterioration of some of the colored illustrations—known as illuminations—including a white pigment that has turned black. The edges of the illustrations have suffered the most deterioration, but in some cases the entire picture has been affected. Fortunately, a few unaffected areas provide a vital baseline for comparison between original and current conditions. The manuscript itself is in poor condition, with the brown/black ink of the text clearly visible through the back of the thin paper and perhaps even corroding it.

Clark and Gibbs set up their Raman microscope by coupling an optical microscope to a spectrometer with an intensified photodiode array detector. The light sources were an argon-ion laser emitting at 488 and 514.5 nm at a power of 5 mW and a krypton-ion laser producing 5 mW at 647.1 nm. In some instances, the risk of laser damage to the pigments was reduced by adding a 10% neutral-density filter, which cut the power at the pigment surface to 0.5 mW.

The laser light was focused by the microscope objective to a spot approximately 1 µm in diameter. The Raman scattering from the sample was collected by the objective and directed to a monochromator and the detector array. In this manner, individual grains of the pigment were examined and their spectral responses compared to known spectra of commonly used pigments of that era and chemicals suspected of contributing to the degradation.

"This technique is very fast and can be done in situ," said Clark. "It is usually successful because there are many different vibrational markers (band frequencies, bandwidths, and band intensities) for each pigment." He adds that Raman microscopy for this purpose has been around for some time, but a new generation of equipment from manufacturers such as Renishaw (Wotton-under-Edge, England), DILOR (Lille, France), and Kaiser Optical Systems (Ann Arbor, MI) are transforming the technique, making it quicker and more effective than in the past.

Working with experts at the British Library and referencing past studies of Byzantine manuscripts, the researchers were able to determine that the deterioration of the illuminations has been caused by a transformation of the white lead pigment to black lead (II) sulfide. The most likely source of the sulfur causing the degradation was the polluted atmosphere of London in the late 19th century and the gas lighting used in the British Library until the 1880s. Five pigments also were detected—vermilion, lapis lazuli, orpiment, realgar, and pararealgar. Until now, pararealgar had not been detected on any manuscript and had not been identified in situ and nonintrusively on any historical artifact.

With this work complete, Clark and his colleagues are looking at a range of Oriental art and at the different pigments that were used. He says it is important to see what is happening to particular chemicals and how chemically to reverse the deterioration process. The treasures under study include pigments on pottery, ceramics, textiles, and Egyptian papyri. As the value of this conservation approach is realized, Clark thinks that the technique of Raman microscopy will soon make its way into many of the world's museums.

About the Author

Conard Holton

Conard Holton has 25 years of science and technology editing and writing experience. He was formerly a staff member and consultant for government agencies such as the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority and the International Atomic Energy Agency, and engineering companies such as Bechtel. He joined Laser Focus World in 1997 as senior editor, becoming editor in chief of WDM Solutions, which he founded in 1999. In 2003 he joined Vision Systems Design as editor in chief, while continuing as contributing editor at Laser Focus World. Conard became editor in chief of Laser Focus World in August 2011, a role in which he served through August 2018. He then served as Editor at Large for Laser Focus World and Co-Chair of the Lasers & Photonics Marketplace Seminar from August 2018 through January 2022. He received his B.A. from the University of Pennsylvania, with additional studies at the Colorado School of Mines and Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University.