Single-pixel-sized spectrometer holds huge possibilities for biosensing

Researchers at North Carolina State University (NCSU; Raleigh, NC) designed and demonstrated a spectrometer that’s just a few square millimeters in size, which is several orders of magnitude smaller than conventional technologies and sensitive enough to accurately measure a broader range of wavelengths than is currently possible.

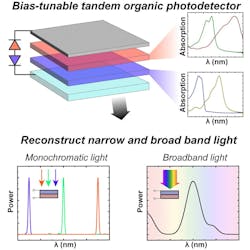

It involves a tiny photodetector that senses light after it interacts with a target material. And when different low voltages are applied, the team can manipulate which wavelengths—ranging from ultraviolet to near-infrared—the photodetector is sensitive to (see video).

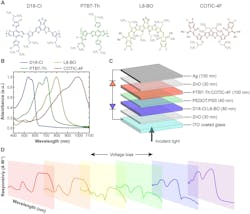

“In our case, the voltage sweep is relatively small, from about -0.8 to 0.2 V,” says Brendan O’Connor, a professor in NCSU’s Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering. “More specifically, we get the unique photoresponse with applied voltage by having two photosensitive cells stacked on top of each (in a tandem), designed in such a way that the efficiency of charge extraction from each cell depends on the applied voltage.”

Each cell has a unique spectral absorption character, despite some overlapping absorption. This combination from each of the cells allows the spectrum of the incoming light source to be reconstructed after the detector is calibrated or trained.

Spectrometer design

The team’s spectrometer design comes after previous work on polarization-sensitive photodetectors.

“We realized we could use polarization for color selectivity in a photodetector design,” O’Connor says. But the team also discovered that achieving hyperspectral detection with their design “resulted in a rather complicated device stack,” which prompted them to turn toward the periphery of miniaturized spectrometers.

“We saw a review in Science on miniaturizing spectrometers,” O’Connor says. “The discussion on reconstruction spectrometers inspired us to figure out how we could do this with organic detectors.”

After testing their device, the team looked at older work relating to amorphous silicon detectors with a similar design. But it wasn’t used for spectral detection; it was for two- and three-color detection. They also found a similar design that used organic semiconductors. But again, it was only for two optical bands.

“Our design is unique because the materials used in the cell were specifically selected and implemented in our device design to lead to spectrometer capabilities,” O’Connor explains.

A need for speed?

The team’s spectrometer can be made as small as a single pixel and operates very quickly; the entire process happens within less than a millisecond. And it’s already proven to be as accurate as conventional spectrometers, with sensitivity that rivals commercial photodetector devices.

“Moving to a single photodetector element allows simple miniaturization that’s very difficult to achieve using dispersive optics and filters,” O’Connor says, noting the design doesn’t need additional optical elements. “Having a monolithic, two-terminal device allows for simple integration into an array of detectors.”

While akin to a charge-coupled device (CCD) camera in a smartphone, the team’s device doesn’t need RGB color filters. Instead, each pixel has spectrometer capabilities, which paves the way for a compact imaging spectrometer.

There have been demonstrations using an applied voltage to a photodetector to achieve a reconstruction spectrometer, including some that use semiconductors, O’Connor points out. But his team’s work produced a much more “simple and effective design that outperforms these recent remonstrations in many respects, including speed, power, bandwidth, and resolution,” he says.

Wide range of applications ahead

A wide array of applications are possible for the tiny spectrometer. It could be used in laboratory settings—as a microscope attachment, for example—as well as in manufacturing for quality control, and in health monitoring and other biosensing applications. There’s also potential for consumer products, such as those used to treat skin conditions, food quality detection, or to identify early stages of plant disease. Other possibilities include monitoring car exhaust, inspecting dyes used in foods and clothing, verifying health supplements, or security and optical encryption.

“It’s exciting to think about what is possible when a powerful piece of equipment that’s usually relegated to research laboratories can be put into people's hands,” O’Connor says. “Scaling this technology down to consumer products would bring this type of scientific value to everyday uses.”

What’s next?

O’Connor says the team is already working on several improvements. Among them: broadening the device’s operating bandwidth and making the detector even faster, as well as improving the detector calibration and reconstruction algorithm.

“While we can reproduce a broad array of incoming light spectra, the detector could improve capturing fine spectral features,” he says. “We believe this is more of a challenge in the reconstruction model rather than the detector itself.”

The team also plans to translate the detector to an imaging array. “The photodetector we demonstrated isn't too different from an organic light-emitting diode (OLED) fabricated as an array in active-matrix light-emitting diode (AMOLED) displays. Although our case should actually be simpler in many ways,” O’Connor says. “We'd like to develop an array that can take fast images capturing spatial and spectral information and, if fast enough, videos. This would open up a wide range of applications. There are far-reaching opportunities with this technology and we’re excited to see where it goes next.”

About the Author

Justine Murphy

Multimedia Director, Digital Infrastructure

Justine Murphy is the multimedia director for Endeavor Business Media's Digital Infrastructure Group. She is a multiple award-winning writer and editor with more 20 years of experience in newspaper publishing as well as public relations, marketing, and communications. For nearly 10 years, she has covered all facets of the optics and photonics industry as an editor, writer, web news anchor, and podcast host for an internationally reaching magazine publishing company. Her work has earned accolades from the New England Press Association as well as the SIIA/Jesse H. Neal Awards. She received a B.A. from the Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts.