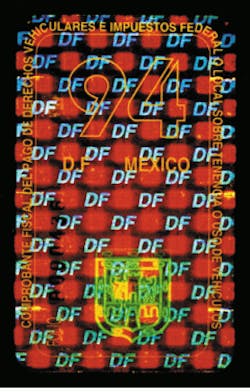

Take any major credit card, hold it in the light, and tip it back and forth. There, on a patch of metallized plastic, a small image will shimmer and float, its eye-catching presence the salesclerk’s assurance—as well as the cardholder’s—that the card is not a fake. Similar holograms, durable and cheaply produced, are being used in increasing numbers throughout the world for security purposes, all based on the premise that holograms are hard to counterfeit. They are found on everything from whiskey bottles to ID cards, from concert tickets to price tags, from textile labels to government documents to money. Of all the security features added to credit cards over the years, holograms are what have best withstood the wiles of tamperers and forgers. But do they guarantee authenticity?

No, according to Steven McGrew, president of New Light Industries Ltd. (Spokane, WA), a company developing hologram anticounterfeiting technology. Although even the most-sophisticated hologram can be reproduced given enough time, money, and effort, the standard mass-produced hologram is, he says, rather easy to counterfeit. He reports that the Secret Service presented [at Holo-pakHolo-print 97, a conference on holographic security held in November 1997 in Orlando, FL] actual counterfeits of the dove found on the VISA card. "Most of them were bad, but some were very good, enough to fool some holographers," he says, adding that the better ones would easily fool any salesclerk.

The credit-card hologram is considered an optical variable device (OVD), a class of devices used for security and authentication that include gratings, conventional image-based holograms, and stereograms (which, as the observation point is shifted, can show action in the manner of a movie). At its simplest, an OVD is no more than a grating that gives rise to a colorful patch of light. In a more complex form, it may be made up of hundreds of two-dimensional computer-generated images, each viewable from a slightly different angle, the sum of which depicts a three-dimensional object created entirely in software.

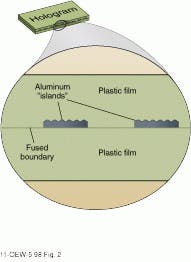

Most mass-produced holograms are embossed on plastic, then back-coated with a reflective metallic layer (see Fig. 1). Small embossed holograms can be produced for no more than a fraction of a cent each.There is one characteristic that all OVDs share: they cannot be duplicated using conventional printing technology. The ubiquitous ink-jet printer, capable of counterfeiting currency and checks, is useless to the potential counterfeiter of OVDs. But although the equipment needed to forge an OVD is not offered at local computer stores, someone with enough knowledge and persistence can put together a setup good enough to be in business.

Counterfeiting techniques

An embossed hologram can be duplicated in one of four ways. The first, mechanical copying, involves delaminating the hologram from its backing so that the embossed surface is exposed. By electroless-nickel-plating the surface, a metal master is created that can be used to emboss new holograms identical to the original. The second method, contact copying, is exactly that: a piece of glass covered with photoresist is laid on the hologram and exposed with laser light. By plating the resist with nickel, then separating and cleaning the resultant piece of metal, a master is created. In the third method, called two-step copying, reconstructed laser light from the hologram is used to make another hologram which, due to its position during exposure, differs from the first. This new hologram can now be used as a source of reconstructed light to create a duplicate of the original, from which the all-important metal master can be made.

But it is the fourth method, says McGrew, that gives rise to the best counterfeits. It is not hard to understand why. This method, called re-origination, involves creating a new hologram from scratch. A lab equipped for this task is most likely a sophisticated operation. McGrew recalls one of the counterfeits he saw at the Orlando conference: "Someone had to carve a very nice dove," he says, referring to the model imaged in the hologram.

Making a secure hologram

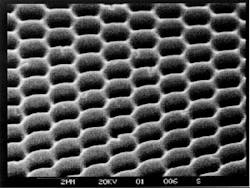

To foil these techniques, McGrew and others at New Light Industries have developed a hologram that is hot-stamped as an array of small metallized dots and then bonded to a coating (see Fig. 2). Beneath the hologram, and visible between the dots, is an ordinary printed image that can be made different for each hologram.If an attempt is made to delaminate the hologram for mechanical copying, the dots separate unevenly from the coating, destroying the hologram. Both contact and two-step copying are rendered impractical by the presence of the printed image underneath, which would unavoidably appear in the counterfeit. The hologram itself can be made of a well-known human subject, making re-origination more difficult.

"I would like to emphasize that, so far, holograms have served their intended purpose of impeding counterfeiters," says McGrew. "Bad counterfeits have been caught. But I also want to emphasize that counterfeiters have big budgets and keep improving their techniques and technologies, so it is important to keep improving the counterfeit deterrence of holograms."

There are many ways to make a hologram more se cure, according to Jeffrey Weil, lab director at Holographic Dimensions (Miami, FL), a maker of security OVDs. "A straight forward technique," he says, "which is a very good one, in fact, is just to make your hologram as complicated as possible." In addition to harboring the illusion of motion and other effects, Weil explains, an embossed hologram can be made in which portions of the image differ in relative color. Add a complex substrate and a coating with distinctive lacquers and dyes, and the cumulative result is a hologram almost impossible to duplicate. For certain applications, special mounting adhesives can increase security (see photo at top of this page).

But what about the tired salesclerk who approves a fake with nary a glance?

The best way to avoid human error, says Weil, is to pass the task of verification over to a machine. A hologram can be made so that it contains an element readable by an optical sensor. Not only does this bypass the drowsy clerks of the world, but, as its most important properties are often hidden to the eye, this sort of hologram can be extremely difficult to counterfeit. A bar code is a simple example of a machine-readable element; more complicated are covert images containing subtle phase information.

Hologram registry

And what if a crook tries to dupe a legitimate hologram manufacturer into becoming an unwitting co-conspirator? A custom hologram, bought and paid for, could contain an obscure portion that, when snip ped out, just happens to pass for something else. Or, more simply, a manufacturer, not knowing what else is out there, could be made to produce a counterfeit perfect in its every detail.

"A practical tool has been developed to prevent this sort of problem," says Lewis Kontnik, president of Reconnaissance International (Denver, CO), a company that serves as secretary to the International Hologram Manufacturers Association (IHMA). The IHMA, he ex plains, has compiled a hologram database and specimen registry called the Hologram Image Register (HIR). Holograms produced by the sixty-odd worldwide members of the IHMA are categorized in the HIR by type, image properties, text, and other qualities. A member company seeking to make a hologram uses the register to verify that it is not unwittingly about to make a counterfeit. "The HIR is searchable," Kontnik says, "and can be directly connected with law-enforcement activities."

About the Author

John Wallace

Senior Technical Editor (1998-2022)

John Wallace was with Laser Focus World for nearly 25 years, retiring in late June 2022. He obtained a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering and physics at Rutgers University and a master's in optical engineering at the University of Rochester. Before becoming an editor, John worked as an engineer at RCA, Exxon, Eastman Kodak, and GCA Corporation.