SEMICONDUCTOR LASERS: Electrical microcavity produces long-wavelength laser light

Thanks to the Purcell effect, small microcavities formed by dielectrics, metals, or nanophotonic structures can produce low-power-dissipation, ultrasmall, and potentially ultrafast electrically injected lasers due to strong confinement of the optical mode or strong light-matter coupling in the cavity. Examples of microcavity lasers include vertical-cavity surface-emitting lasers (VCSELs) with dielectric-confined cavities, lasers based on plasmonic microcavities, and microcavity quantum-dot-based lasers.

Now, researchers in the Institute for Quantum Electronics at ETH Zurich (Zurich, Switzerland) have borrowed concepts from electronics and microwave technology to produce an ultrasmall microcavity laser consisting of a terahertz quantum-cascade gain region confined by an inductor-capacitor (LC) resonant electronic circuit.1 The effective mode volume for this laser is smaller than that previously reported for any electrically pumped microcavity laser, according to the researchers, and has the potential to be scaled to even smaller mode volumes.

Fabricating the microcavity

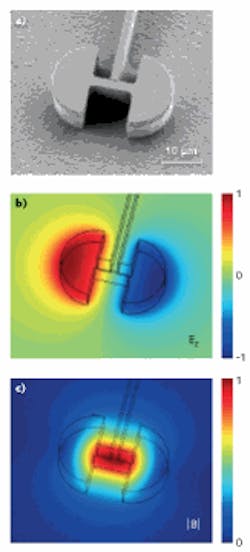

The circuit-based resonator cavity consists of two half-circular-shaped gold capacitors with radii of 10 µm connected by a short (3 µm width and 10 µm length) line structure acting as an inductor (see figure). This symmetric LC resonator—with dimensions chosen as a compromise between size, losses, and ease of fabrication—naturally defines a virtual ground for the resonance frequency in the middle of the inductor; the resonator is connected to the bonding pad for electrical pumping of the active medium, which is placed between the capacitor plates. The gain medium is an 8 µm thick active region of a quantum-cascade laser (QCL), designed for operation at 1.45 THz (207 µm). The electric field is antisymmetric with respect to the axis of symmetry of the structure; the magnetic field is concentrated around the inductor.

Measured output for the LC laser operated at 10 K reached a maximum of approximately 80 pW at 1.55 mA. The spectrum shows a single emission line at 1.477 THz, which is close to the design wavelength of 1.45 THz; however, fabrication parameters could be altered to extend lasing to anywhere from the terahertz region to the near-IR region.

Such ultrasmall, single-mode, strong-mode-confinement devices with low power dissipation could be integrated with hot-electron bolometers to produce arrays of sensitive heterodyne receivers for demanding applications—radio astronomy, for example. “In a broad sense, the use of resonant electronic circuits in optical sources and detectors adds a new level of flexibility in the resonator design,” says ETH Zurich professor Jerome Faist. “It also opens up the possibility of leveraging the strong Purcell effect obtained by these small cavities for enhanced emission or detection.”—Gail Overton

REFERENCE

1. C. Walther et al., Science 327, pp. 1495–1497 (Mar. 19, 2010).