Very high-peak-power lasers catch up with reality

ANTOINE DURET AND EMMANUEL MARQUIS

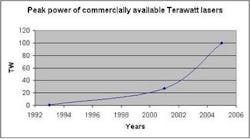

High-peak-power lasers have been viewed for a long time as laboratory systems, nurtured by optical researchers trying to beat world records for peak power (see Fig. 1). Changes are coming, however, as the latest generation of commercial systems introduce new beam-control technologies and computer interfaces.

Key technologies

Unlike classical Nd:YAG lasers based on oscillator and amplifier configurations, high-peak-power units are based on the well-known chirped-pulse amplification (CPA) technique introduced by Gerard Mourou in the 1980s. These lasers use a scheme in which very short pulses coming from an oscillator are stretched to picoseconds, amplified to high energy, and recompressed back in the femtosecond domain, usually with the use of gratings. This principle, common to radar signal processing, avoids high-power density that would cause damage in the amplification section. The oscillator is usually based on "modelocking" to offer very short pulse duration.

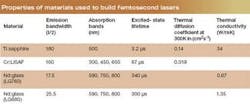

In these kinds of lasers, two materials are now widely used as the amplifier medium: Nd:glass and Ti:sapphire. Nd:glass lasers were the first commercial systems that enabled very high peak powers of 100 TW. Unfortunately, the thermal conductivity of Nd:glass does not allow repetition rates above 0.1 Hz at terawatt levels. This amplifier medium is now being replaced by Ti:sapphire, which allows much higher repetition rates at equivalent peak-power levels. A record was broken in 2002 when a 26-TW system operating at 10 Hz was installed at the Central Research Institute of Electric Power Industry (CRIEPI; Tokyo, Japan; criepi.denken.or.jp), making this laser the most powerful, commercial 10-Hz system ever delivered. Ti:sapphire also has a large emission bandwidth that allows a much shorter pulse duration than Nd:glass lasers (durations less than 30 fs are commercially available today). Other lasers based on chromium-doped lithium strontium aluminum fluoride (Cr:LiSAF) crystals were developed, but they are limited by the unconventional wavelength needed to pump the crystal (see table).

Critical points

The energy source for high peak power amplifiers is radiation in the 500-nm region delivered by a pump laser. Numerous companies have introduced a wide range of high-energy green pumps based on Nd:Glass or Nd:YAG technology. The beam-profile quality and the stability of the pump laser are of critical importance for the overall performance of the terawatt laser. Another key element is the pulse recompression stage. As energy rises, manufacturers use bigger and bigger gratings to handle the energy density. Above a certain level, this compressor must be used under vacuum to prevent ionization of the air when the short pulse propagates.

The most powerful lasers (typically 100 TW) also have to deal with cooling issues: with the growing average powers used to pump amplifier crystals, temperature and induced stress must be carefully managed. Several advanced laboratories have introduced cryogenic cooling with either closed-loop helium or open-loop liquid nitrogen as a way to overcome this problem (see Laser Focus World, October 2005, p. 65).

A final issue is the difficulty in increasing repetition rates of terawatt lasers beyond 10 Hz: pump lasers must deliver both high pulse energy (several hundreds of millijoules to several joules) and high beam quality--but these two parameters are hard to maintain at high repetition rates due to thermal management issues.

Recent advances

As the pace of R&D for terawatt lasers accelerates, new products and concepts are frequently introduced.

A major breakthrough in the last few months was the introduction of JEDI from Thales Laser, the first 100-Hz diode-pumped green laser source dedicated to femtosecond-laser pumping (see Fig. 3). The Institut National de la Recherche Scientifique (INRS; Varennes, QC, Canada; www.inrs-ener.uquebec.ca/) has recently acquired a complete diode-pumped 100-Hz terawatt laser from Thales for its Advanced Laser Light Source (ALLS) project. Opening a wide field of research for scientists, this system delivers 4 TW at 30 fs.

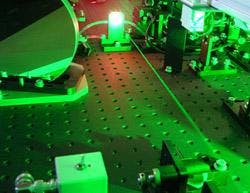

THALES Laser has also introduced cryogenic-free cooling technology for 10-Hz systems, allowing tremendous peak powers of 100 TW without the complexity and high price of cryogenic cells, and with excellent beam-focusing capability (see Fig. 4). Two of these systems were ordered in the United States and South Korea in the last quarter of 2004 for a variety of ultra-high intensity applications such as plasma physics.

Applications

Though typical applications of multiterawatt lasers are in fundamental research, more and more systems are used for environmental, medical, or even defense-related purposes.

Self-guided filament generation is one of the main applications of the Teramobile system, a 6-TW mobile system installed in a truck by Thales Laser in 2001. A sophisticated optical setup allows the resulting very high-peak-power density around the beam focus to cause the creation and propagation of filaments of ionized particles along the beam path. These filaments can be used to guide lightning (see Laser Focus World, February 2005, p. 11). The excitation of the filament molecules can also generate a continuum beam for LIDAR detection of various molecular species in the atmosphere.

Higher peak power lasers still tend to find applications closer to fundamental research. The laser installed at CRIEPI in Japan is used for laser wakefield acceleration: the intense electric field contained in the pulse accelerates charged particles to relativistic speeds and very high energies (1-MeV protons). Laser wakefield acceleration is a promising approach to enable compact electron accelerators to generate ultrashort bunches of electrons for probe analysis of matter.

Another way to probe matter is hard x-ray generation by focusing a terawatt pulse on a target. The very short wavelength (0.1 nm) and pulse duration allow time-resolved measurements of fast phenomena with atomic spatial resolution.

In the past two years, 100-Hz diode-pumped ultrafast lasers with lower peak power (below 4 TW) have been gaining attention for their higher average power and repetition rate, better stability, and easier beam manipulation, making a number of applications more accessible compared to their 10-Hz counterparts.

For instance, the 100-Hz system at the INRS yields increased average power while maintaining acceptable x-ray conversion efficiency, thus allowing a tenfold decrease in the necessary exposure time for a three-dimensional biomedical image (see Laser Focus World, June 2004, p. 38). Linear particle accelerators (LINACS) are also finding interest in 100-Hz systems as they enable an increase in the injection rate of accelerators with high-quality ultrashort electron bunches--expected to be a major step in the development of free-electron lasers to generate ultrafast coherent x-ray laser pulses.

The future

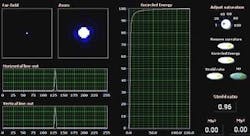

Now that terawatt lasers are moving out of the laboratory and into commercial instruments, ease of use, the man/machine interface, reliable performance, and durability are important parameters. The new generation of terawatt systems must focus on the development of supervision software and synchronization tools like the master clock to control every element of the laser, with minimum setup time for more efficient operation.

ANTOINE DURET is marketing and applications engineer and EMMANUEL MARQUIS is business development manager at Thales Laser, Domaine de Corbeville, RD 128, 91404 Orsay CEDEX, France; email: [email protected]; www.thales-laser.com.