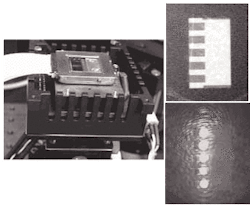

The thin-film geometry of vertical-cavity surface-emitting lasers (VCSELs) allows them to be fabricated in large arrays with relative ease. Engineers at Protiveris (Rockville, MD)—a company developing tools for the emerging field of proteomics—have taken advantage of the emitters' simplicity and designed them into 1 × 64 arrays customized for a benchtop protein-biochip system (see figure).

Intended to detect biomolecular interactions, the biochip system has at its heart a silicon nitride microcantilever array chip with a gold surface. As described by Tim Seeley, vice president of engineering, biochemists at Protiveris customize the gold surfaces of the cantilevers in such a way that they respond to the introduction of various biochemical substances by deflecting to a degree that depends on the biochemistry involved. When mounted in a custom microfluidics device, the microcantilevers on the chip are positioned so that groups of cantilevers reside in several discrete compartments, or cells. Each cell has its own microfluidics inlet and outlet so that each cell can perform a different biochemical test.

"We measure the cantilever deflections by illuminating each cantilever (the cantilevers are on the same 250-µm spacing pitch as the VCSELs) with a dedicated VCSEL from the VCSEL array module," explains Seeley. "The reflected light from the cantilever's gold surface is presented, through beamsplitting optics, to a position-sensing-device array whose output is monitored in near-real time and recorded for post-data-acquisition analysis."

The individually addressable VCSELs are single-mode and emit at 850 nm. An integrated temperature-sensing diode and an external thermoelectric cooler maintains a constant temperature. The VCSEL array's common cathode is die-bonded to a metallized beryllium oxide heat spreader, providing both an electrical return path and efficient heat transfer to the package body. A fused-silica microlens array mounted on a positioning stage focuses the laser light; the microlens array can be removed if needed.

First developed at Oak Ridge National Laboratories (Oak Ridge, TN) in 1996 and IBM (Zurich, Switzerland) in 1999, the microcantilevers are label-free biosensors (meaning that no labeled biomolecules, dyes, or stains need be attached to the cantilevers). Their sensitivity permits the use of nanoliter-sized sample volumes, helping to conserve valuable chemicals. In addition to biochemical use, the cantilevers are used to detect inorganic substances such as hydrogen or mercury and physical properties such as viscosity and humidity.

"The major advantage the VCSEL array module yields for this application is the ability to perform multiplexed tests," says Seeley. "That is, a different test can be performed in each microfluidics cell and one or more cells can be used as a test-control function to monitor environmental effects such as temperature and pH."

The tests initially pursued by Protiveris will be pharmaceutical: for example, so-called ligand fishing (in which a molecular receptor is tried against many types of ligands to find a match), comparative protein expression, and toxicity profiling.

About the Author

John Wallace

Senior Technical Editor (1998-2022)

John Wallace was with Laser Focus World for nearly 25 years, retiring in late June 2022. He obtained a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering and physics at Rutgers University and a master's in optical engineering at the University of Rochester. Before becoming an editor, John worked as an engineer at RCA, Exxon, Eastman Kodak, and GCA Corporation.