The advent of color inkjet printers has given counterfeiters and brand pirates a straightforward and inexpensive means to ply their trade. For this reason, holograms and other diffractive optical elements—which require an expensive laser interferometric setup to reproduce—have become the security mark of choice for credit cards, software labels, and other uses. But such holograms are made of polymer; unless they can be integrated into a plastic product, they must take the form of an adhesive label. If a method for forming a hologram onto metal could be perfected, metal parts and devices could be marked directly in a secure manner.

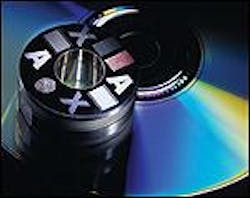

Conventional holographic systems do not have enough power to mark metal. Simply upping the power of a conventional laser does not work either; the resulting thermal effects would obliterate the micron-sized features required for a holographic mark. Femtosecond lasers ablate material directly and thus can potentially create diffractive elements in metal. Engineers at TNO Industrial Technology (Eindhoven, The Netherlands) have developed an ultrafast holographic system that marks metal with gratings having structures as small as 200 nm. The marks can have grating blaze angles that vary by location, creating color effects.Grating pixels can be built up into diffractive letters and numbers (as in these figures), barcodes, or other remotely readable codes. The resulting holographic watermarks can be mass-produced such that they cannot be distinguished from one another. Other applications being pursued at TNO Industrial Technology include the holographic modification of friction resistance on metal parts such as pistons, the fabrication of metal compact-disc stampers out of long-wearing tool steel instead of nickel, making injection molds that transfer holographic patterns to plastic parts, and structuring surfaces so that they have self-cleaning properties.

About the Author

John Wallace

Senior Technical Editor (1998-2022)

John Wallace was with Laser Focus World for nearly 25 years, retiring in late June 2022. He obtained a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering and physics at Rutgers University and a master's in optical engineering at the University of Rochester. Before becoming an editor, John worked as an engineer at RCA, Exxon, Eastman Kodak, and GCA Corporation.