Transmissive architecture enables low-cost mini LCD

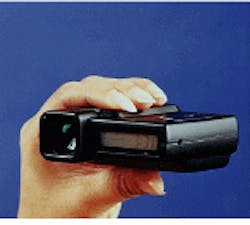

Kopin Corp. (Taunton, MA) has introduced the latest in an increasingly long line of miniature displays. Aimed at low-end consumer applications, these twisted-nematic liquid-crystal devices have the advantage of an entirely integrated light source, made possible only because they are transmissive displays. Unlike some competing products, Kopin's CyberDisplay may be able to achieve full color and good gray scale without the need for particularly fast switching or color filters (see photo).

The CyberDisplay is manufactured with VLSI processing. Simple electrode structures are deposited on a silicon wafer covered with a proprietary chemical layer that makes it possible to lift the circuitry cleanly off the backplane after processing. The circuitry is subsequently transferred onto a glass substrate, thereby enabling the display to operate transmissively, giving the Kopin device two major advantages.

First, the device uses a built-in light-emitting-diode-based backlight. All competing displays are reflective and must, therefore, have light coupled in from a source at the front or side, which increases the total volume of the system.

Second, the front surface of a transmissive display is unidirectional, in that light does not have to enter from the front—it must only leave that way. Kopin has exploited this characteristic by putting an array of imaging microlenses on the display to allow it to be viewed without any further optics despite its tiny 0.24-in. (diagonal) dimension.

The Kopin display is unusual not only because of its transmissive architecture. Unlike most competing LCDs, it is based on a slow liquid crystal in which the gray scale can be controlled in an analog fashion—as the voltage across the crystal is varied, the amount of light that can pass through changes, too. In contrast, the faster commercial ferroelectric liquid crystals operate in binary mode—that is, light is either allowed to pass through or not. Hence, in these devices gray scale must be produced using time-division multiplexing. For an eight-level image, this means updating the display eight times for each video frame. Bright pixels are kept on for most of those updates, less-bright pixels are on for only a few, and so on.

Use of twisted-nematic materials has enabled Kopin engineers to avoid using multiplexing and to keep their system simple. They also sidestepped manufacturing problems inherent to ferroelectric liquid crystals, which are much less tolerant of variations in cell thickness than nematics are. The relatively low prices of CyberDisplay evaluation kits and single evaluation units reflect this ease of manufacture.

The display is currently available only in monochrome with 320 × 240-pixel resolution. A full-color version is, however, expected within the next year. According to Glen Kephart, vice president of marketing at Kopin, the company will use a special backlight containing a triplet of red, green, and blue LEDs that will be spread over the entire display using a reflective/diffusive "mixing bowl." To get a full-color image, the red, green, and blue LEDs have only to be turned on sequentially for each frame, timed to coincide with the correct LCD data. From a power-consumption point of view, this design has the advantage that no light is filtered out—the right color is simply produced as needed.

At the low cost end of the market, Kopin has the first commercially available display, though others may be waiting in the wings. Companies working with ferroelectric displays have been concentrating on more specialized markets, such as head-up displays and optical correlators. At the other end of the market, Texas Instruments (Dallas, TX) seems to be aiming its micromechanical digital mirror device at applications such as projection displays, where high optical performance is the main requirement.

About the Author

Sunny Bains

Contributing Editor

Sunny Bains is a contributing editor for Laser Focus World and a technical journalist based in London, England.