On meeting schedules and budgets

When the beauty of engineering gets lost in delays

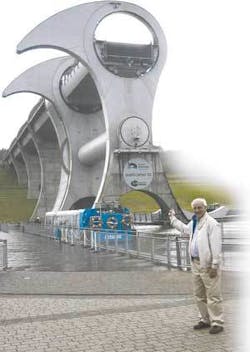

The Falkirk Wheel has been labeled an engineering marvel, a unique one-of-a-kind, an exciting example of 21st Century engineering and Scotland’s most recognizable Monument to the Future. On the day I visited in May, fighting an incipient gale blowing down the Forth River valley, it was imposing.

Completed in 2002 as part of Scotland’s Millennium celebration, an £85 million project restored the Forth & Clyde (a 1790, 38-lock canal) and the Union (an 1822, one-level canal) that link Edinburgh to Glasgow in a sea-to-sea ship canal. The canals intersect at Falkirk where a £22 million project (£5 million for the Wheel), a first-of-its kind 1800-ton, spoon-shaped seesaw boat-lift raises 250 tons of canal boat in a water-filled gondola from the Forth & Clyde canal 85 feet to the Union canal, while lowering an identical gondola with boat from the Union canal. As both gondolas contain the same weight (even with varying passenger loads, thanks to Archimedes’ principle of boat displacement) only 1.5 kW of electricity is needed to turn the Wheel. Actually the 500-ton weight of boats and water are easily turned by two small cogwheels. There’s a lot more to it than that simple explanation and, if you are interested, you can learn more at the website www.thefalkirkwheel.co.uk.

While I was suitably impressed by the brilliant Scottish engineering that went into this project I was even more im-pressed when I learned that the projected five-year canal project, shortened to three years of actual work due to bureaucratic delays in funding approval, was completed on time and on budget. Now that’s something you rarely hear in this era of cost overruns and project delays. Look to Boston’s infamous 15-year Big Dig, still not totally completed and bearing a $15 billion price tag (it was originally estimated at $2.8 billion and 5 years).

My hosts for the visit, understandably proud of the engineering that produced the Wheel, were a little non-plussed at my less-than-ebullient view of this accomplishment as opposed to my outspoken praise for the project completion timing and adherence to budget.

It has become too common today to set a budget and a schedule as a moving target, much of which can be laid at the feet of concurrent engineering practices. Even NASA, the progenitors of meeting budgets-remember JFK’s famous “man-on-the-moon in ten years speech”-now consistently miss target goals and make routine visits to the U.S. Congress for additional funding.

One of my university degrees is in Production Engineering where we were inculcated with target setting, goal achievement, and budget responsibility. Having this drilled into me, I became an incipient anal-retentive adhering to completion dates and budget restraints. As the years progressed and the culture of laissez-faire business practices filtered down to the production floor I became a little more flexible (although some on the production staff at ILS would argue otherwise) as budgets became less sacred and goal flexibility more prevalent.

Many, like me, are questioned about the need to make targets on budget, and they are looked on as being “out-of-touch” with reality today. Maybe so, but I do know that accomplishing what you said you could, when you said you would, with what you were given is not a bad thing. Besides, the headache you get from the too-tight halo you wear in the project review meetings is a pleasant pain.

David A. Belforte

[email protected]