“While the results are only preliminary, we have shown that SORS holds a lot of potential in biomedical applications of Raman that may not have been considered before,” says Vanderbilt University graduate student Matthew Keller. A recent paper by Keller and his advisor, Dr. Anita Mahadevan-Jansen, demonstrated for the first time that spatially offset Raman spectroscopy (SORS) is effective at discriminating between two layers of soft tissue.1

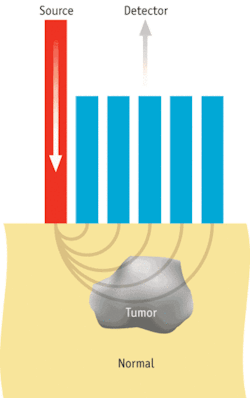

SORS, first demonstrated by Pavel Matousek et. al.,2 can probe deeper than conventional forms of Raman thanks to its use of a source-detector (S-D) offset between light delivery and collection elements. Its primary biological application of SORS has been detecting the strong, unique Raman signature of bone through several milimeters of soft tissue.

The work by the Vanderbilt group is motivated by the issue of margin evaluation after partial mastectomy procedures for early-stage breast cancer treatment. Doctors must ensure that no cancer cells are found in the outermost 1 to 2 mm of the removed tissue during these procedures to minimize the risk of the cancer recurring. Because Raman spectroscopy can classify breast tissues very accurately,3 “it made sense to see if SORS could detect breast tumors under 1 to 2 mm of normal tissue, as would be needed for margin analysis,” says Keller.

They used a simplified setup of normal breast tissue layers placed on top of breast tumors for their initial experiments. Thus, they were able to observe increasingly stronger contributions to the collected Raman spectra from the tumor layer compared with the normal tissue layer as they increased S-D offset. They observed this effect for normal tissue thicknesses from 0.5 to 2 mm, indicating that the technique would be applicable to the analysis of breast surgical margins. As part of their experiment, they also showed that a conventional Raman probe could not gather the same depth-related information they saw with a SORS setup.

Breast cancer surgeon Ingrid Meszoely says she can envision several potential uses for this technology in her work. “The goal of a curative operation for malignancy is to excise the entire tumor with margins that are both grossly and microscopically free of tumor,” she says, explaining that it’s often difficult to recognizing an involved margin during surgery. “A technology that allows the surgeon to accurately assess margin status at the time of the operation could potentially improve surgical outcomes with regard to tumor excision.” She also notes that the accuracy of image-guided needle biopsies are hindered by sample size. “Occasionally an area of malignancy may be in close proximity to the benign tissue that has been sampled and therefore goes undetected,” she says–adding that this technology could enhance malignancy detection during the biopsy procedure.

The researchers acknowledge that much work lies in front of them prior to a successful clinical application of SORS. “The biggest obstacle going forward will be seeing how well we can detect very small pockets of cancer cells or tumors with highly irregular shapes,” says Keller.

REFERENCES

- M. D. Keller, et al., Opt. Lett. 34, 926 (2009).

- P. Matousek, et. al., Appl. Spectrosc. 59, 393 (2005).

- S. K. Majumder et al., J. Biomed. Optics 13, 054009 (2008).

About the Author

Barbara Gefvert

Editor-in-Chief, BioOptics World (2008-2020)

Barbara G. Gefvert has been a science and technology editor and writer since 1987, and served as editor in chief on multiple publications, including Sensors magazine for nearly a decade.