With the upcoming presidential election, the war in Iraq, and economic issues all vying for valuable floor time in the U.S. House and Senate, other critical issues are getting pushed aside this year. One in particular that appears to be in jeopardy is the reauthorization of the Small Business Innovative Research (SBIR) program, a government-wide initiative that gives small businesses an opportunity to develop promising technologies that serve the government’s research and development needs.

With a proven 25-year, $18 billion track record and more than 85,000 projects funded, SBIR reauthorization (an extension for the program to continue) would appear likely. But no deal in Washington is complete until the ink dries on the signature line. Back in 2000, the program actually shut down for 36 hours until a reauthorization rider was slipped into an omnibus bill that passed.

The SBIR program requires that the 11 agencies with the largest R&D budgets (including the National Institutes of Health) reserve 2.5% of their R&D budgets for the three-phase program: Phase I feasibility testing (contracts awarded up to $100,000 over six months, Phase II product R&D (contracts up to $750,000 over two years), and Phase III commercialization (no SBIR funding, companies seek private or other federal agency support; unlimited time).

Debate will heat up in the coming months over several key components of the program, namely participation by venture-capital-backed companies, increasing allocation of R&D dollars from 2.5% to 5%, and boosting Phase I awards to $150,000 and Phase II amounts to $1 million. All parties involved will need to come to some consensus before the end of September when the program is scheduled to “sunset” or expire.

Targeting venture capital

The hot button for SBIR reauthorization is eligibility of venture-capital firms to compete for Phase I awards, but this issue is nothing new. After three Congresses and five years, the House and Senate still haven’t reached a consensus. The debate stems from a 2003 ruling by an SBA administrative law judge that required the Small Business Administration (SBA) to begin looking more carefully at the makeup of companies applying for SBIR grants. The ruling states that venture-capital firms cannot be considered individuals for the purpose of satisfying the ownership criteria for the program. This action has made a number of companies, particularly in the biomedical area, ineligible for SBIR funds.

One Hill observer says that the venture-capital issue will boil down to whether Congress wants to emphasize the “S” or the “B” in SBIR. At this point the House and Senate don’t agree on whether they should change the program to address the venture-capital issue. A bill introduced last fall by John Kerry (D-Mass.), chairman of the Senate Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship, and ranking member Olympia Snowe (R-Maine) that tried to bridge a middle ground passed in the Senate but failed in the House. An alternative bill was approved in the House, but failed in the Senate.

This year the Senate has yet to hold hearings on SBIR reauthorization, although an aide to Kerry on the Small Business Committee says Kerry is committed to reauthorizing the program. The House Committee on Small Business, chaired by Nydia Velasquez (D-NY), has held several hearings with the majority of witnesses from larger companies or groups seeking to reinstate eligibility for venture-backed firms.

Biomedical-industry supporters say the 2003 ruling, which defines a small business as one with fewer than 500 employees, independently owned, and operated by individuals, limits the development of blockbuster medical devices or treatments. “The government will paint itself into a corner and only fund lesser projects” if the eligibility rules don’t change, says Ellen Dadisman, spokesperson for BIO, the Biotechnology Industry Organization.

But small-business proponents worry that the program’s original intent, to stimulate technological innovation among small businesses while giving the federal government cost-effective solutions to its technical and scientific challenges, will get lost as will opportunities for startups.

“When you start changing the framework of a program for small businesses, to what extent will you block out the sunlight for those small businesses?” asks Edsel Brown, assistant director for SBA’s Office of Technology. “It’s not a matter of do we favor venture-capital-firm participation, but when. It seems to be moving further and further up in the process.” Currently, companies seek private funding during Phase III.

The cost of commercialization

Much of the debate grows out of the high costs faced by companies developing medical devices and drug therapies. The price tag to bring a drug to market can easily exceed $1.2 billion over a decade. Companies entering into the NIH SBIR program face unique challenges.

To this end, NIH, which has awarded $5 billion to more than 5000 small businesses since the program started, has taken advantage of SBIR rules that allow each federal agency to tailor the program to best serve its needs and it is paying off. A recent National Research Council report found that 40% of SBIR-funded projects reach the marketplace. 1 NIH SBIR program enhancements include:

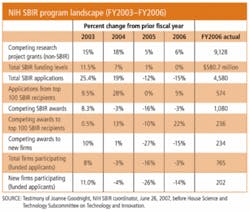

- Higher than normal Phase I and II grants: in FY2006 Phase I awards averaged $137,000 and Phase II $833,000 (see table; from testimony of Joanne Goodnight, NIH SBIR Coordinator, June 26, 2007, before the House Science and Technology Subcommittee on Technology and Innovation);

- Competing Renewal Phase II awards: given on a discretionary basis for projects such as drugs, medical devices, or imaging protocols that require clinical evaluation, federal regulatory approval, and/or testing. Amounts are $1 million annually for up to three years

- Niche Assessment Program: assists Phase I awardees map out market opportunities and assess end-user needs;

- Commercialization Assistance Program: one-on-one business counseling for Phase II awardees to develop and implement business strategies to commercialize SBIR-funded projects. Opportunity to present plans to targeted group of investors; and

- Pilot Manufacturing Assistance Program: guides companies in decisions related to such topics as scale up, quality control, prototyping, and facility design.

- Preference given to firms with no previous NIH SBIR support and firms that respond to agency-specific priorities.

NIH also recently requested the National Research Council undertake an empirical assessment of the 2003 ruling to see which companies were excluded or likely to be excluded from the SBIR program as a result and what impact of the ruling is having currently and would have had between 1992 and 2006.2

To lessen impact of the venture-capital issue, some observers have suggested creating a separate program for innovation development at NIH. “NIH is concerned about the path to commercialization. Instead of trying to fit a square peg in a round hole, let’s look at a commercialization program,” suggests James Morrison, a senior advisor for the Small Business Technology Council.

But the chance that someone will devise an entirely new program that addresses the needs of NIH is unlikely. At this point it’s unclear where on the spectrum the House and Senate will meet to reauthorize SBIR, but as Brown notes, “it would be devastating to have a gap in the program.”

REFERENCES

1. National Research Council, An Assessment of the Small Business Innovation Research Program at the National Institutes of Health, Washington, D.C., p.18, (2007)

2. Ibid, p.28

About the Author