When removing a tumor, a surgeon can’t always distinguish cancerous tissue from healthy tissue. “I use predominantly tactile information to tell where the lump is,” says Gooitzen Van Dam, MD, PhD, a surgical oncologist at the Groningen University Medical Center (The Netherlands). “I feel, and then use the electric knife to dissect the tumor.”

But feeling around is not always enough. “It’s particularly difficult to tell tumor from nontumor in breast tissue because of the mass of tissue and gland tissue,” says Van Dam. One day though, advanced optical imaging could clearly delineate between diseased and healthy areas.

The development of one such technology began nearly a decade ago. In 1999, Brad Rice, PhD, started working at Xenogen (Alameda, CA), where he’d been hired to design instrumentation to image light-emitting reporters in tissues of animal models used in preclinical research. “We wanted to develop an optical system optimized for in vivo applications,” Rice says.

Two Lights to Follow

Bioluminescent reporters, like firefly luciferase, generate light without excitation light. Luciferase can be integrated in the DNA of mammalian cells to track bacteria, cancer, or stem cells in research animals. Bioluminescent reporters can even make light-emitting organisms. For example, scientists can insert the firefly-luciferase gene in front of the rat insulin promoter (RIP-luc) in the mouse genome, and use light emission to study insulin’s production.

“We wanted to see light at the lowest possible levels from bioluminescent reporters,” Rice explains. In 2000, that desire emerged as the IVIS 100, which is an imaging chamber designed primarily for rats and mice. This device uses a large CCD camera 25 mm across, which is cooled to –100°C to reduce thermal noise. The system quantifies captured light in physical units. “To measure tumor growth over time, for instance,” says Rice, “you need absolute calibration, such as the intensity in photons per second from a specific region.” So Xenogen scientists developed a proprietary calibration scheme.

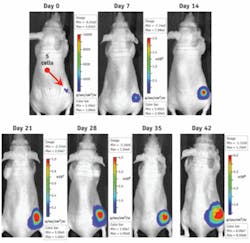

With this system, researchers can image inside animals. “If a tumor cell is tagged and located just under the skin, you can detect a single cancer cell,” says Rice. “At the center of a mouse, say 1 to 1.5 centimeters deep, you can’t see one cell but maybe 1,000 or 10,000, and that’s still a very small tumor, much less than 1 mm across.”

Scientists also use fluorescent probes, such as green fluorescent protein, that need excitation to emit light. So Xenogen released a fluorescence kit, which includes an external lamp, a filter wheel to select specific wavelengths of excitation, and a filter wheel inside the imaging chamber to select wavelengths to capture. This system works in the epi-illumination mode: excitation light comes from the top and emitted light is captured from above.

Rice and his colleagues, though, faced problems from autofluorescence, which is the natural fluorescence of tissue, because it creates background signals. That spurred Xenogen—by then owned by Caliper Life Sciences (Hopkinton, Mass.)—to develop the IVIS Spectrum, which would keep the high-sensitivity bioluminescent capabilities of previous IVIS systems, but improve the fluorescent capability.

Autofluorescence comes mainly from visible-light excitation. So Rice—now senior vice president of systems R&D at Caliper—and his colleagues focused on excitation light in the near-infrared, about 650 to 900 nm. They designed the Spectrum with 10 excitation filters and 18 emission filters, the latter covering 450 to 850 nm. “This gives researchers the flexibility to test different wavelengths,” says Rice.

The Spectrum also includes an optical switch to change from epi- to transillumination, which brings the excitation light from under the animal and captures emitted light above it. “This increases sensitivity for probes in deep tissue,” Rice says, “because the autofluorescence gets trapped under the animal.” The Spectrum also uses a large custom-designed lens, more than 120 mm across.

The Spectrum’s filter set enables spectral-unmixing methods in software, which increases sensitivity by at least 10 times. “You can scan multiple images and move through a sequence of filters to map out the spectral response of the animal or probe,” Rice says. “Then the software helps to separate the probe signal from autofluorescence.” The Spectrum also provides three-dimensional tomography to help pinpoint the location of bioluminescent or fluorescent signals within an animal.

Optics for operating

IVIS technology also spurs ideas of potential clinical applications. Four years ago, Van Dam used an IVIS 100 for preclinical specimens, with the bioluminescence helping him to examine tissues. “We had a vision of using it in the clinic, but how was somewhat unclear, although we immediately envisioned near-infrared, intra-operative fluorescent imaging to be the key to success,” he says.In December 2007, Van Dam upgraded to the Spectrum, which he has used to analyze breast-cancer specimens. “Some of the current tests for detection of cancer in lymph nodes from the breast provide conflicting results,” he says, “but the Spectrum collects results that are not visible to the naked eye.” As a result, the Spectrum might improve the cancer detection, as has been shown in preliminary tests on patient samples. Consequently, tissue could be removed in surgery, examined in the Spectrum, and more tissue removed until the samples show no cancer—meaning that the surgeon had passed the tumor’s edge. Van Dam predicts that the Spectrum could support both the surgeon as well as the pathologist in so-called image-guided resection and histopathology of cancer.

One day, an imaging system similar to IVIS might even be used in real time during surgery. This would be an open-air fluorescent imaging system, says Peter Lassota, PhD, Caliper’s divisional vice president of oncology. “Then, it could be used for guidance during surgery in humans.” Making such an advance, though, might be more of a cultural challenge than a technical one. “Here you have to win the acceptance of regulatory agencies and physicians who will be performing these surgeries,” Lassota says.

As this story shows, however, advances in optical technology depend on exploring new approaches. Moreover, such advances require experts with widely ranging skills.

About the Author

Mike May

Contributing Editor, BioOptics World

Mike May writes about instrumentation design and application for BioOptics World. He earned his Ph.D. in neurobiology and behavior from Cornell University and is a member of Sigma Xi: The Scientific Research Society. He has written two books and scores of articles in the field of biomedicine.