Lens-free microscopy platform shows promise for rapid gout diagnosis

A team of researchers at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) has developed a portable, lens-free microscopy system that can diagnose gout (the most common type of inflammatory arthritis), and could allow many more primary care doctors to screen for the disease.

Related: Compact devices compete with high-end instruments

The research was led by Aydogan Ozcan, UCLA's Chancellor's Professor of Electrical Engineering and Bioengineering and associate director of the California NanoSystems Institute, and John FitzGerald, a UCLA clinical professor of rheumatology.

Gout occurs when uric acid levels in the blood increase to the point that the acid crystallizes, leaving crystal deposits in the joints, tendons, and ligaments that trigger severe inflammation. The disease is caused by a combination of factors, including diet, medication and genetics, and it occurs more commonly in those who consume red meat, drink large amounts of beer, and are overweight.

The definitive test for gout calls for a doctor to draw joint fluid from a patient and then use a device called a compensated polarized light microscope to identify uric acid crystals in the sample. But recent studies have shown that primary care doctors usually opt to make their diagnoses without performing the procedure. In addition, polarized light microscopes are bulky, weigh more than 20 lbs., and cost $10,000–20,000 or more. They also have a relatively small field of view, which can make it time-consuming to examine a large sample, and can produce unreliable test results. The examiners' ability to detect crystals can also vary widely depending on their level of training.

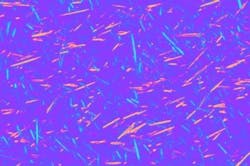

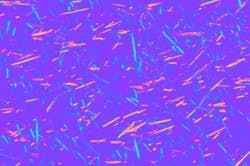

But the research team's platform, based on lens-free on-chip microscopy, can perform wide-field imaging without the need for lenses. It uses holographic imaging to produce high-resolution images of the crystal-like objects—the telltale signs of gout—in the patient's fluid sample.

The technology works by sending a stream of light through a polarizer, through a sample of the fluid on a microscope slide, and then through another polarizer before it reaches an image sensor microchip, a component also found in mobile phone cameras and webcams. The image sensor captures the holographic diffraction pattern produced by the sample and feeds it to a computer with software that can quickly generate an image of the sample. The platform can use the entire active area of the image sensor chip—about 20–30 mm2—allowing for rapid analysis of larger volume of samples. It also can be used at the point of care and in clinical settings with limited resources, Ozcan says.

The technology could ultimately be used to diagnose other conditions that are caused by crystals forming in bodily fluids and that are currently diagnosed using conventional polarized light microscopes, such as kidney stones.

Full details of the work appear in the journal Scientific Reports; for more information, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/srep28793.