Rigid endoscope technology covering hyperspectral imaging gets a facelift

Researchers from Tokyo University of Science and Japan’s National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST), in collaboration with teams from Japan’s RIKEN research institute and the University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria in Spain, have developed a technique for near-infrared (near-IR) hyperspectral imaging (HSI) under a rigid endoscope that covers wavelengths from the visible to 1600 nm (see Fig. 1 and video).

“This technology is expected to be put to practical use as a nondestructive and non-labeling identification technology for objects that cannot be judged by the human eye or objects in deep locations,” says Dr. Toshihiro Takamatsu, a senior researcher at AIST.

HSI is an effective healthcare tool, given its ability to view hidden tissues and other hard-to-reach areas deep in the body to acquire more detailed information. This approach can also cover full spectrums of light intensity in each pixel in an image; conventional imaging techniques are limited to specific wavelengths. But HSI devices aren’t perfect, either. They have trouble in over-thousand-nanometer wavelengths, the research team notes. Sensitivity suffers at those higher wavelengths, and it can be difficult to correct chromatic aberration, which occurs when a lens can’t gather all wavelengths to a single converging point.

The AIST-led team’s rigid endoscope is capable of guiding near-IR light. The setup incorporates a supercontinuum light source that can extract any wavelength of light (from the visible to near-IR) and an acousto-optic tunable filter to emit specific wavelengths. A liquid lens focuses on each wavelength as it is switched, and an integrated camera offers sensitivity in the 450- to 1170-nm range.

“In this system, wavelength sweep is performed on the light source side and images are captured at each wavelength to construct hyperspectral imaging data,” Takamatsu explains.

System advantages

Near-IR wavelengths are known to be more transparent with organic components than visible light. The wavelength region above 1000 nm can be analyzed for components because absorption of molecular vibrations appears in this region. Near-IR HSI can acquire near-IR spectra for each pixel of a camera, Takamatsu says, in turn enabling component analysis with positional information.

“Our approach for near-IR HSI under a rigid endoscope enables analysis of objects in a narrow space,” Takamatsu says.

In their work, detailed in Optics Express, the team recorded classification by the system’s neural network of seven different targets achieved an accuracy of 99.6%, in addition to a recall of 93.7%, and specificity of 99.1% when the wavelength range of over 1000 nm was extracted from HSI data as train data.

Imaging the future

Looking to the future, Takamatsu’s team is now working around some challenges that plague conventional rigid endoscopes, including long imaging acquisition times. Currently, chromatic aberration problems for such endoscopes require refocusing each time the wavelength is switched. The process also boosts computation time because extra wavelength information is also acquired and must be analyzed.

To overcome this, the researchers are developing an algorithm to select specific wavelengths that are effective for discrimination and analysis.

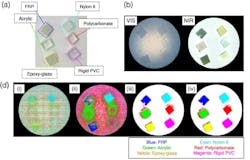

The new technology is well suited for the industrial field, where it can be applied to composition analysis of 3D organic objects such as resins and artwork (see Fig. 2). In the medical field, the setup could visualize targets buried deep in tissues—for example, blood vessels and nerves—in a limited space, such as in laparoscopic surgeries.

About the Author

Justine Murphy

Multimedia Director, Digital Infrastructure

Justine Murphy is the multimedia director for Endeavor Business Media's Digital Infrastructure Group. She is a multiple award-winning writer and editor with more 20 years of experience in newspaper publishing as well as public relations, marketing, and communications. For nearly 10 years, she has covered all facets of the optics and photonics industry as an editor, writer, web news anchor, and podcast host for an internationally reaching magazine publishing company. Her work has earned accolades from the New England Press Association as well as the SIIA/Jesse H. Neal Awards. She received a B.A. from the Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts.