BIANCA MIGLIORI, MALIKA S. DATTA, and RAJU TOMER

Light-sheet microscopy (LSM) is emerging as a highly effective method for rapid volumetric imaging of both fixed and small living samples. While the concept of LSM was introduced more than a century ago,1 the technique has emerged as an important imaging modality only during the past two decades2 facilitated by parallel advances in lasers, detectors, computer hardware, and genetic labeling methods.

At this point, LSM has already enabled such unique experimentation capabilities as the capture of cellular dynamics in developing embryos; mapping of the structure of entire intact, chemically cleared organs; and revelation of functional dynamics in the brains and nervous systems of small, transparent model organisms.

Let's take a look at two recent advances in LSM—CLARITY-optimized light-sheet microscopy (COLM) and spherical aberrations-assisted extended depth-of-field (SPED)—that are facilitating significant advances in neuroscience research by enabling unbiased brain-wide mapping of structure and function and their interrelationships, which is one of the primary goals of such recent high-profile strategies as the U.S. Brain Research through Advancing Imaging Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) Initiative. Then, we'll briefly discuss future challenges in the field.

LSM basics

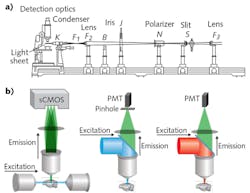

The premise of LSM involves illumination of a sample from the side with a thin sheet of light, and detection of emitted signal with an orthogonally arranged wide-field imaging system (see Fig. 1). The optical sectioning is achieved by the confinement of illumination to the imaging plane of interest. This configuration provides two main advantages: Minimal energy load, resulting in low photobleaching and phototoxicity; and high imaging speeds, owing to the simultaneous detection of the entire illuminated optical plane by fast sCMOS or CCD cameras. Meanwhile, LSM images more than two orders of magnitude faster than other standard microscopy techniques, such as confocal and two-photon microscopy—and at greater depths than confocal with comparable optical parameters (see table). Three-dimensional (3D) image volumes can be acquired either by moving the sample through the fixed optics step-wise, or by synchronously scanning the aligned light-sheet and detection objective through the stationary sample.

These low-energy-load and high-speed capabilities make LSM ideally suited for long-term imaging of live samples. Indeed, LSM has been successfully used to capture the embryonic developmental dynamics of small transparent model organisms such as zebrafish, C. elegans, and Drosophila larvae; for capturing the high-resolution details of subcellular processes; and for brain-wide mapping of neuronal activities in small model organisms. However, steep challenges have remained in achieving rapid, high-resolution imaging of entire intact organs such as mouse brains, and in volumetric imaging of sufficient speed to capture millisecond-scale neuronal activities across entire vertebrate nervous systems. Now, COLM has arrived to solve the first of these challenges, while SPED addresses the second.3,4

COLM: Fast, high-res for large, intact systems

Advances in tissue clearing are providing unprecedented access to large intact organs, including brains and nervous systems. Among the highly effective methods to have emerged over the last decade are Scale, CLARITY, SeeDB, CUBIC, iDISCO, and uDISCO.5 Most of these involve a cocktail of chemicals to dissolve and remove membrane lipids (the main culprits of light scattering) and an optical smoothening step (by incubating in a specific refractive index [RI]-matching liquid).

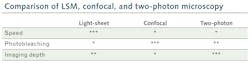

For example, tissue clearing with CLARITY starts with the perfusion of a tissue sample by a cocktail of acrylamide, bisacrylamide, formaldehyde, and a thermal polymerization initiator. This is followed by a thermally initiated (by incubating at 37°C) polymerization reaction, which results in a highly crosslinked meshwork of hydrogel fibers and amine-containing biomolecules. Lipid membranes are then removed either by passive thermal clearing in a buffered SDS solution at 37°C3 or by an active electrophoretic process6—the result is an intact, highly transparent tissue-hydrogel hybrid. Combining these clearing methods with innovative genetics and viral vectors-based labeling approaches is providing unparalleled access to the structure, molecular, and functional architecture of intact tissues.A COLM system includes at least three major innovations that are absolutely necessary for high-resolution imaging across a sample. First, an optically homogeneous sample-mounting framework minimizes optical aberrations, especially across the sample depth (see Fig. 2). A clarified intact organ is mounted in a cuvette made of specific transparent material with matching RI. The cuvette is then attached to a xyz-theta stage by a set of adapters (see Fig. 2b) inside the sample chamber, which is filled with a matching RI liquid. This mounting strategy mitigates the effect of changes in RIs in the detection paths, and also allows the use of appropriate immersion objectives for detection (e.g., CLARITY-optimized long working-distance objectives).

Second, we implemented a synchronized detection-illumination procedure, and demonstrated, for the first time, its utility in achieving higher imaging quality and depth by reducing the out-of-focus background (see Fig. 2c). We did this by synchronizing the line-by-line detection of sCMOS camera chips with fast, pencil-beam scanning of the sample to generate a virtual light sheet.

Third, we developed a novel, adaptive parameter-correction procedure to adjust for misalignments (of the light-sheet and detection focal plane) introduced by significant optical variances across the sample. The method involves quick calibration to automatically estimate the alignment parameters at defined imaging positions distributed sparsely across the sample (see Fig. 2d). Linear interpolations of the alignment parameters in all three dimensions facilitate high-quality imaging throughout the sample. The result is one of the first demonstrations of an automatically self-correcting adaptive LSM.

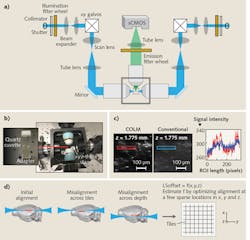

These optimizations laid out the principles for rapid, high-resolution imaging of clarified organs. We successfully used COLM to capture, for the first time, high-resolution maps of entire intact mouse brains and nervous systems, and also human brain samples (see Fig. 3). This approach is compatible with other tissue clearing methods as well, and has enabled an entirely new class of experimentations for a fundamental understanding of brain architecture.8

SPED breaks a speed barrier

Many live-imaging experiments, including calcium imaging of neuronal activity, require very high-speed capture of entire 3D volumes. Light-sheet microscopy, owing to simultaneous wide-field detection of the illuminated planes, enables high planar imaging speeds, especially in comparison to confocal and two-photon microscopy.

Typically, 3D image volumes are acquired by moving the sample stage step-wise along the z-axes (depth), or by synchronously moving the aligned light-sheet and detection objectives through the stationary specimen. Both of these approaches are fundamentally limiting because of the significant masses that must be moved at high frequency. In contrast, other methods such as light field microscopy (LFM)9 and multi-focus microscopy10 achieve high speeds by acquiring the entire 3D volume in a single image—although at some cost of resolution and sample-size constraints, and requirements for complex volumetric deconvolution.A crucial property of LSM is that the final optical point spread function (PSF) is the result of the intersection of the light sheet and the detection objective PSF (see Fig. 4a). The lateral resolution is thus determined by the detection objective's numerical aperture (NA), whereas the axial resolution derives from the thickness of the illumination light sheet. Therefore, by axially elongating the detection PSF while keeping the lateral extent constant, it becomes possible to acquire an entire 3D volume at very high speed and resolution by rapidly scanning the light sheet alone, and bypassing the need for a piezo motor to move the sample or the objective.

Building on the mechanisms that commonly produce undesirable spherical aberrations, we demonstrated this principle by developing a scalable, novel method to obtain elongated PSF. By interposing a transparent block of high-RI material between the objective and sample, tuning of PSF elongation became a matter of manipulating easy-to-understand physical parameters.

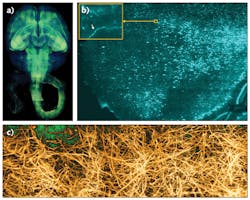

By eliminating the need to move any physical object (apart from galvo scanners, which can achieve several-kilohertz frequency), SPED allows volumetric imaging at speeds limited only by camera acquisition rates. Thus, its performance will improve along with advances in detector technologies. We demonstrated the system through many proof-of-principle experiments in biology applications, including very high-speed imaging of neuronal activity across entire nervous systems, and subcellular resolution imaging of large, intact clarified brains.

The future starts here

COLM enables rapid high-resolution imaging of intact transparent mouse brains and nervous systems, while SPED has proven able to perform long-term, high-speed, and high-resolution live imaging of cellular and functional dynamics in embryos and brains. Coupled with advances in labeling methods for specific cell types, these methods are facilitating unbiased mapping of the molecular, structural and functional architectures of brains.

Further advances in optical methods may include integration with super-resolution microscopy approaches (such as stimulated emission depletion [STED] microscopy) and improvements in imaging procedures and real-time data processing for yet higher-speed imaging. However, progress in imaging methods requires corresponding advances in data analysis and storage. Indeed, commercially successful, scalable platforms such as Spark and Hadoop are useful frameworks for enabling "big data" processing. Similarly, cloud services such as Amazon Web Services (AWS) are democratizing access to scalable storage and computing infrastructures. Adoption of these technologies in biological sciences research will facilitate development of scalable data-analysis tools able to extract knowledge from samples.

Altogether, these are exciting times for bioscience research. Methods such as those described here are really just the beginning for understanding vastly complex biological systems such as brains.

Acknowledgements

Bianca Migliori and Malika S. Datta contributed equally to this article. The authors would like to thank Ola Hermanson and Karl Deisseroth for related discussions.

REFERENCES

1. H. Siedentopf and R. Zsigmondy, Ann. Phys. (Berlin), 10, 1–39 (1903).

2. E. H. Stelzer, Nat. Methods, 12, 23–26 (2015).

3. R. Tomer, L. Ye, B. Hsueh, and K. Deisseroth, Nat. Protoc., 9, 1682–1697 (2014).

4. R. Tomer et al., Cell, 163, 1796–1806 (2015).

5. D. S. Richardson and J. W. Lichtman, Cell, 162, 246–257 (2015).

6. K. Chung et al., Nature, 497, 332–337 (2013).

7. H. U. Dodt et al., Nat. Methods, 4, 331–336 (2007).

8. T. N. Lerner et al., Cell, 162, 635–647 (2015).

9. N. Cohen et al., Opt. Express, 22, 24817–24839 (2014).

10. S. Abrahamsson et al., Nat. Methods, 10, 60–63 (2013).

Bianca Migliori is a visiting PhD student and research associate, Malika S. Datta is a graduate student, and Raju Tomer is assistant professor, all in the Department of Biological Sciences at Columbia University, New York, NY; e-mail: [email protected]; http://tomerlab.org.

![FIGURE 5. (a) A depth color-coded maximum intensity projection (top) and volume rendering (bottom) depict a SPED imaging dataset acquired from a zebrafish larva expressing nuclear localized GCaMP. (b) A 1-mm-deep SPED image shows a clarified Thy1-eYFP mouse brain [4]. FIGURE 5. (a) A depth color-coded maximum intensity projection (top) and volume rendering (bottom) depict a SPED imaging dataset acquired from a zebrafish larva expressing nuclear localized GCaMP. (b) A 1-mm-deep SPED image shows a clarified Thy1-eYFP mouse brain [4].](https://img.laserfocusworld.com/files/base/ebm/lfw/image/2016/12/1612lfw_tom_f5.png?auto=format,compress&fit=max&q=45&h=203&height=203&w=250&width=250)