Two recent projects may improve the prospects for applications of terahertz (far-infrared) radiation. A British-based invention uses a single broadband laser with lines in the visible to produce highly stable, tunable emissions in the terahertz region. Another scheme, developed through a collaboration between three U.S. institutions, uses relativistic electrons to produce a very high average-power output of 20 W. Though further work is necessary for both research teams—to optimize the former system and to characterize timing jitter in the latter—current results are promising.

The terahertz radiation spectral band is a region that has slipped through the crack between optical and electronic signal generation because it is too high in frequency to be produced by electronic systems and too low in frequency to be produced by conventional optical sources. Terahertz radiation is potentially very useful, however. Though some claim it will have applications in telecommunications, it looks most promising as a source for medical imaging, nondestructive testing, and security screening; not only is the radiation nonionizing, but human tissue, plastics, clothing, and semiconductors are all transparent to it.

High power from electrons

The high-power source is the result of a collaboration between researchers at the National Synchrotron Light Source (part of Brookhaven National Laboratory in Upton, NY), the Advanced Light Source Division of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley, CA), and Jefferson Laboratory's Free Electron Laser Facility (Newport News, VA).1 Their scheme involves the production of bunches of electrons that are spaced to provide a terahertz signal. This idea is not new, but their implementation of it avoids two pitfalls of previous systems: low repetition rate (producing low average power) and long electron bunch times that limit the frequencies that can be achieved.

The team's energy-recovered linear accelerator (ERL) uses short electron bunches (about 500 fs) produced by a free-electron laser, which are then compressed as the bunches are curved around by an electric field. Usually, this curving—a deceleration—would result in the electron bunches losing energy. In the ERL, however, superconducting radio-frequency cavities recover the energy of the spent bunches, thus making the current orders of magnitude higher than in conventional linear accelerators. The resulting terahertz emissions are close to 1 W/cm of average spectral power density into the diffraction limit.

Possible problems of the system are coherent detection and a low signal-to-noise ratio caused by timing jitter and current fluctuation. The researchers are working on solutions for these.

Tunable terahertz

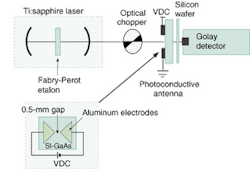

The other new source, developed at the Institute of Microwaves and Photonics at the University of Leeds (Leeds, England), involves using two wavelengths from a single Ti:sapphire laser source to produce high-quality terahertz radiation through photomixing.2 Uniquely, the method uses a Fabry-Perot etalon of a given thickness to pick out wavelengths from the broadband source that have the ideal frequency difference to produce a given terahertz emission. The photomixing process is enhanced by the fact that the spatial mode matching of the two beams is ideally matched, thanks to having been generated by the same source. In addition, fluctuations in terahertz frequency are kept to a minimum as changes in one wavelength are automatically compensated for by changes in the other.

The proof-of-principle system used a microscope coverslip as the etalon (see figure). The optical chopper was used to modulate the signal, after which photomixing took place on a large-aperture triangular antenna fabricated on semi-insulating gallium arsenide. The resulting radiation was detected by a Golay cell, the output of which was then amplified. To test the system's ability to image, parallel strips of aluminum foil were sandwiched between paper and acetate. These strips showed up clearly as dips in the detected signal.

Leeds University recently patented this invention. In their filing they suggest that microfabricating the etalon will allow the source produced to be fully tunable. They have not yet produced such a system, however. In addition, the power of the overall setup is still very low—in the nanowatt region—with conversion efficiency estimated at just 10-9. By optimizing the optics and improving the photomixing antenna (perhaps by replacing it with nonlinear crystals), the research team hopes to make significant improvements.

REFERENCES

- G. L. Carr et al., Nature 420, 153 (Nov.14, 2002).

- M. Naftaly et al., THz 2002 (IEEE), Cambridge, England, 140, (Sept. 9-10, 2002). Extended version to appear in IEEE Microwave Transactions.